Acknowledging the critical link between forest rights and climate change, the Government of Odisha has taken pioneering steps to protect the significant tribal and forest-dwelling population of the state. Neelima Mishra explains what this important measure means for tribal communities, forest-dwellers and the ecosystem

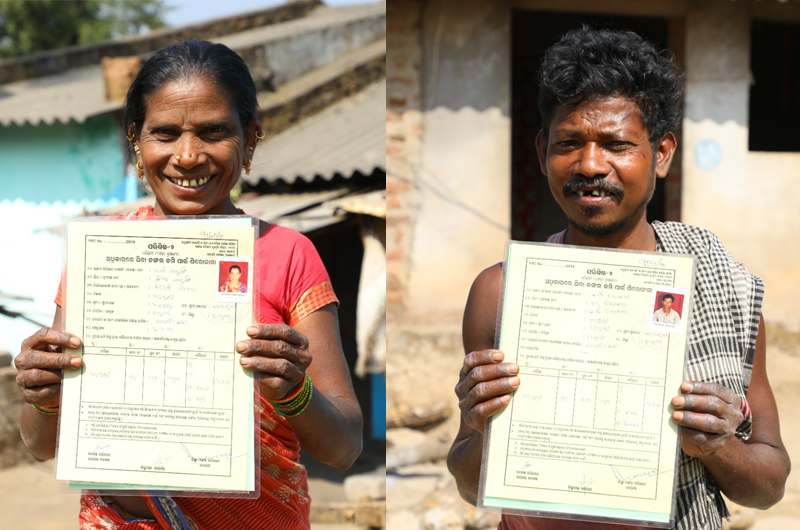

Odisha recently launched an ambitious forest land rights scheme for its tribal communities and forest-dwellers, focussed on safeguarding the knowledge of indigenous peoples, ensuring protection of the forest ecosystem, enabling sustainable livelihood practices and taking measures to reduce climate change. The Mo Jungle Jami Yojana (MJJY), which can be translated as My Forest Land Scheme, provides indigenous peoples rights over the forest land they have been dwelling in for ages so that they can play a pivotal role in protecting rapidly decaying forests and counter the challenges of climate change while relying on the jungle for their livelihoods. MJJY reflects the view of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs that indigenous peoples are “the custodians of our Earth’s precious resources.”

The delicate balance between the traditional knowledge of indigenous people, forest ecosystems, territorial rights and climate change is a topic of increasing significance, as nations grapple with the consequences of climate change. Land and its natural resources are vital assets for rural communities and indigenous peoples to meet fundamental necessities such as food, water, fuel-wood and medicinal plants. They also provide a sense of security, social standing and a safety buffer. For many communities, land is historically, culturally and spiritually significant too.

There is growing evidence worldwide that tenure-secure forestlands are associated with reduced deforestation, carbon emissions and other ecosystem-service benefits. A report titled Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, jointly published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Fund for the Development of Indigenous Peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean (FILAC), shows that improving the tenure security of these territories reduces deforestation rates. For example, in Bolivia, Brazil and Colombia, the average deforestation rate between 2000 and 2012 inside tenure-secure indigenous land was 0.15 per cent, 0.06 per cent, 0.04 per cent while the rate outside indigenous land was 0.43 per cent, 0.15 per cent, 0.08 per cent, respectively.

According to the FAO/FILAC Report, regions possessing land rights exhibited carbon emissions between 42.8 and 59.7 million metric tons lower than comparable Amazon regions with equivalent environmental conditions and market access. The report’s findings also indicate that the indigenous territories have more species of mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians than in all the country’s protected areas outside these territories, thus showing that indigenous people play an important role in safeguarding biodiversity.

There have been various landmark legislations across the globe acknowledging the rights of indigenous peoples over lands, territories and resources along with related self-governance and participatory decision-making rights, like the 1976 Australian Aboriginal Land Rights Act, the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act 1997 in the Philippines and the Law on the Rights of Consultation of Indigenous Peoples, Peru, 2011.

In India, the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dweller’s Act 2006, commonly known as the Forest Rights Act or FRA, has vested a number of rights on the tribal and local communities, including the right to live off the forest, to use and govern forest resources and the right to hold forest lands for self-cultivation for livelihood or for habitation. Odisha is in the forefront of Indian states pioneering forest rights. Odisha Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik has said, “Indigenous peoples share a symbolic and cultural linkage with forest, land and nature. Protection of the cultural identity of the indigenous peoples along with the conservation and management of the forest resources are the prime duty of my government.”

MJJY was launched on the occasion of the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. It is the only programme in India that complements the efforts for forest-based livelihoods by promoting individual and collective action including environmental conservation and preservation. Explaining the initiative, ST & SC Development, Minorities and Backward Classes Welfare Department Commissioner-cum-Secretary Roopa Roshan Sahoo said “MJJY aims to serve multiple objectives of safeguarding the traditional knowledge, ensuring saturation of individual and community forest rights, preserving biodiversity of forests, sustaining livelihoods through a robust forest economy, conversion of un-surveyed /forest villages and, more importantly, taking measures to reduce climate change. This scheme is significant as Odisha is home to 62 Scheduled Tribes that include 13 Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups.”

While launching the scheme, the chief minister pledged to extend recognition of community rights and community forest resources rights to nearly 32000 villages covering a potential forest area of 35,000 sq km. With this programme, Odisha has shown the way in climate adaptation and mitigation measures by securing the collective entitlements of indigenous peoples and communities to lands, territories and resources.

It is important to understand that land titling for indigenous peoples is not an end in itself, but part of an ongoing process of building sovereignty, security and sustainable resource management and livelihoods as well as dealing with climate crisis. When community lands are effectively protected, progress can be made towards achieving numerous SDGs (sustainable development goals) along with climate objectives. Research also demonstrates the benefits – for people and forests – of secure land and resource rights.

(The writer is a senior consultant to the Poverty and Human Development Monitoring Agency, Government of Odisha. PHDMA, established in 2005, has been working consistently as a monitoring and evaluation organisation dedicated to tracking poverty and human development indicators and assessing the impact of welfare schemes. In recent years, the focus has shifted to collecting human interest stories and people’s lived realities as oral narratives to gauge their socio-economic growth. Sandip Kumar Bal, a content and communications person who has been associated with PHDMA, helped with the story.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux