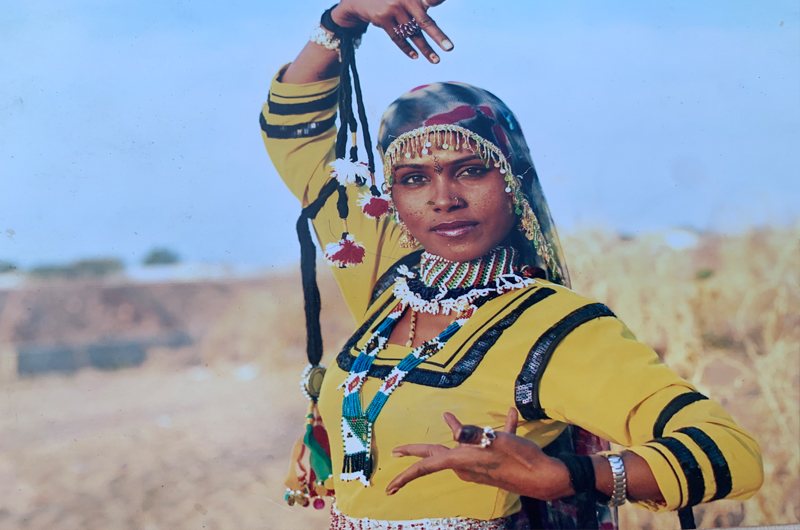

Kalbeliya, a nomadic tribe of Rajasthan, is known the world-over for its famous dance form. Shefali Martins profiles Rakhi Kalbeliya, a prolific performer who has gained popularity as a teacher of the dance

An image of Pushkar Fair or any Rajasthani fair, for that matter, is incomplete without the brightly-clad Kalbeliya dancers. Kalbeliya, a nomadic tribe of Rajasthan, is known the world-over for its famous dance form thanks to noted dancer Gulabo Sapera who put the dance as well as Pushkar on the world map back in the 1980s. Dressed in colourful ghaghras with a black base, the Kalbeliya women’s fast moves and flexibility combined with an enchanting grace has charmed millions of desi and foreign tourists.

Many of the Kalbeliya women today perform all over the world; yet when they return home, they return to lives of poverty and negligence. A prolific performer among them, who has also gained popularity as a teacher of the dance form, is Rakhi Kalbeliya, a resident of Kalbeliya Colony in Ganahera, just out of Pushkar. As you navigate a rather sandy path to her place, the words Kalbeliya Dance Academy painted on the front wall of her house greet you and there youfind Rakhi, who never went to school, conversing in broken but confident English with her overseas students, who come to spend time in Pushkar and learn various dance forms, Kalbeliya or Snake Dance being one of them.

“I have been teaching dance from the age of 13 and have been working at the dance school at Old Rangji Temple in Pushkar for the past 16-17 years. Earlier, the women of our community used to perform, not teach. But now, teaching the dance is becoming very popular,” says Rakhi, who claims to have started the trend of conducting Kalbeliya dance classes in Pushkar.

Rakhi is a self-taught Kalbeliya dancer. It runs in the blood, she says. “My elder sisters used to dance and I would copy them. No one in our community learns this dance. We may teach foreigners and Indians, but it comes naturally to us Kalbeliya women,” says Rakhi. She has toured many countries, including Italy, France, Spain, Austria, Germany, and England multiple times, for performing and conducting dance workshops. She does three-to-seven-day workshops as well as two-month-long tours, the duration depending on the requirement. “You see how in Ajmer we have these smaller places: Pushkar, Ganahera, Pisangan; similarly, in Europe, they have small villages. We tour one village after the other. My former students arrange for the workshops and make the travel and stay arrangements.”

Rakhi has students from overseas who come to learn from her every year, including an American student who has been coming for the past seven years, as well as students from Chile and Mexico. Pushkar gets a lot of overseas visitors round the year including performing artists and yoga enthusiasts. Many of them learn Indian folk and classical dance and then go back to conduct their own workshops in their home country. Rakhi is well aware of the fact that they learn the dance at a very low fee as compared to what they charge back home. “They too need to earn, right,” she says.

Despite boasting of thousands of students from all over the world, Rakhi still lives in a non-electrified house. “Even after all this recognition, we are pretty much where we were. We did get a colony for Kalbeliyas but the facilities remain rather scanty. A water connection has reached my house only six months ago. Before that, we used to get metallic, muddy water from the hand pump,” she says.

Rakhi has toured India extensively for shows. While the organisers make the arrangements and give respect, the pay is not as much. “For a show, besides the travel and boarding arrangements, they typically give Rs 5,000-6,000 for the whole group. On an average, we have a group of 10, and so, this too comes to about Rs 500 a person for an entire evening of performance,” she explains.

But Rakhi is a happy artist. She shows a book on the Kalbeliya Community and excitedly points to its cover, “See, I have been featured in this book in Italian language. I’ve also been a part of a Rajasthani language film. I was married at 21, and my husband Sadhu and his family support my work. Sadhu helps in organising tours and also plays instruments. In fact, it is only after marriage that I’ve started living in a house. I used to live in a tent earlier. My mother still lives in one,” she says.

Rakhi charges Rs 500 an hour for a class. While she does get bookings for classes, they are not regular. In the past three years in particular, there hasn’t been much work for her, but she managed to conduct online classes during the pandemic even though she was pregnant at the time. She is now looking forward to the flow of visitors in Pushkar to be restored to its pre-pandemic days so that her classes can start on a regular basis.

A usual performance consists of the kalbeliya dance, chari dance (dancing while holding a metallic pitcher on the head with fire lit in it), paraat dance (dancing on the edge of a large platter), dancing on nails and on glasses. The movements for some of the dances are rather risky and one can get injured with the slightest loss of balance. “We do get hurt at times, that comes with the deal. This is our Kalbeliya life,” Rakhi proudly says. While the community cannot officially keep the snake (as they used to before it was banned) the snake motif is an integral part of their being. “Our dance itself started with the moves of the snake. The music of the pungi (folk music instrument) is an important part of it. The snake is inseparable from our lives.”

Discussing the generational shift that has come about in the dance, Rakhi says that earlier they did not perform on the stage or in hotels. Performances were locally organised in small villages. Now, there are dances for stage shows, marriage parties and the like.

Rakhi is a mother of three and is excited about her youngest child, her two-year-old daughter Komal learning the dance. “Komal already dances when I dance. I’m sure she will do both – studies and dance. She doesn’t cry when I do a class. In fact, she excitedly joins in. My boys, Durgesh (7) and Jack (5), have started playing folk music. I would like Komal to learn other classical forms of dances like Kathak. I want to educate all my children so that they don’t have to experience the hardships that I have faced,” she says.

Rakhi feels satisfied with the recognition she gets in her community. “The young girls like to emulate what I have done. I have also been able to use some influence to get some work done for my colony. There was no road to reach here till recent years. I spoke to some journalists who wrote about it, and this road was built. Else even a bike couldn’t reach here.” She adds how she contributed to COVID relief work for out-of-work artistes in her area, thanks to her overseas contacts.

Rakhi is happy about being independent. “Women have always worked in my community. Why should we women be dependent on our husbands? We can handle our expenses, and even our children’s expenses. Our hard work should also matter, right?” Rakhi says, adding, “I love my dance. I want to dance my entire life. It is our community legacy, and that must continue.”

Note: The article was written as a part of Sanjoy Ghose Media Awards 2022. The writer is an independent journalist and educator from Ajmer, Rajasthan.

(Courtesy: Charkha Features)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux