Shoma A. Chatterji profiles Sudeep Ranjan Sarkar, the maverick filmmaker, who has won many awards but is hardly known in India

Sudeep Ranjan Sarkar wears many hats. He is a management scholar who, till recently, managed several management institutes in Kolkata. He is an astrologer and a psychiatrist. He is also a film director, writer, actor and editor of six full-length feature films which remain largely invisible to the Indian audience at home. Why? Because he is not interested in getting his films censored and is not bothered whether they’re screened or not. He doesn’t want his freedom of expression, including what he feels necessary for films, such as nudity, erotic scenes and so on, blocked.

Sudeep Ranjan Sarkar is always dressed in suits, has a bunch of glasses he chooses from, wears lots of bracelets and rings with large stones on both hands. He shuns publicity, saying he makes films as a form of self-expression and does not care whether others like them or not. So, it would be apt to define him as an ‘invisible’ filmmaker, surprising in an era and in an industry where being in public view is almost mandatory.

Sarkar mostly shoots his films outside India and uses an iPhone to avoid getting relevant permissions, and yet gets good results. He chooses his cast mainly from theatre artistes, both in India and abroad, and he plays some roles himself. He has a wonderful producer in Rita Jhawar who gives him a totally free hand to make films and also chips in as an actress in some of the movies.

Though Sarkar’s truly out-of-the-box films get hardly any exhibitors in India, they have won a number of international awards. His films use a lot of surrealism and fantasy and have stories of sin and crime from which the protagonist comes out spiritually transformed.

In his first film, Umformung: The Transformation(2014), Sarkar uses the term as a metaphor to compare his two protagonists – a young Buddhist monk and a beautiful and attractive business woman – with German soldiers in World War II who go through a life-changing moment leading to critical questions: Should they escape from the war? Do they owe greater allegiance to country than to themselves? Or, is it the other way round? Should they rescue injured fellow soldiers from certain death? Or leave them to die? Should they face death with courage? Each of these choices transforms the soldiers.

Says Sarkar, “The basic truth the film tries to focus on is the complete irrelevance of worldly affluence and power and the relevance of surrendering everything to what is known as Truth. The film holds spiritual power as supreme. I believe we are not human beings with spiritual experience, rather we are spiritual beings with human experience.”

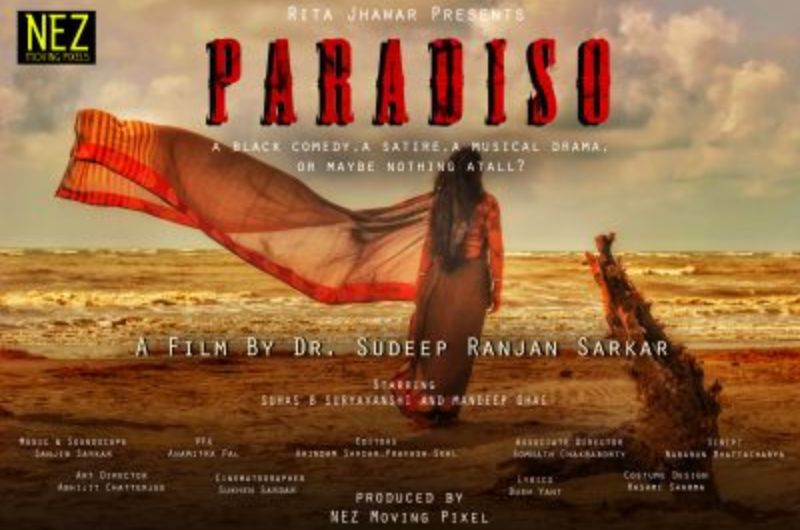

Paradiso(2017) is perhaps one of only two films he has directed which are placed in a fixed space – in or around Kolkata. It is also placed in a certain period – in the turbulent 1960s. Paradiso has more or less a chronological, sequential storyline which, though it sometimes wanders away to other segments, remains focussed on the male protagonist who is almost totally silent through the film.

Says Sarkar, “The film is a non-story. It does not have a classic beginning, or middle, or end. It is a snapshot from an ordinary middle class person’s life and I show the audience whatever might truly happen to this person or to any of us in daily life, and our responses to it.”

In Lust(2018), he said he wanted to make a political statement like George Orwell’s Animal Farm and to point a finger at the hollowness of religious institutions. In his Glorious Dead(2019) he talks about the lurking evil behind the seeming good that we all portray. Death of Spring (2020) won the Best Feature Film Award at the Indian World Film Festival and the award for Best Direction and Best Music at the prestigious Dada Saheb Phalke Film Festival. It was shot in France with a couple of foreign actors. It was made in English. Says Sarkar when asked why: “There was never any compulsion to shoot in India or France. I wanted to show a universal woman, incidentally it was a German actress.”

Sarkar’s latest film Notes To A Lover from Jenny Adams and Her Beautiful Family, which has not been screened yet, was shot during the lockdown last year. The black-and-white movie has absolutely no dialogue. It is about a crippled old lady taken care of quite affectionately by two young women and a young man who appears to be her son. The music in this film is very rich and mood-based. The deep influence of Charlie Chaplin is evident through the film including the dialogue cards that appear between scenes.

“My films are outpourings of my mind. I see the world as cruel, unforgiving, relentless. My philosophies are ensconced in my cinema. But since I feel even cinema as a medium is too small to capture my mind, I move away from all grammar, be it technique, characters, everything. I want to fill every single frame with my overflowing perceptions of this world,” he sums up.

(The writer is a senior journalist and film historian based in Kolkata. She was presented the South Asia Laadli Media and Advertising Award for Gender Sensitivity 2017.)

April – June 2022

from Webdoux

from Webdoux