Bharat Dogra reviews a book about an unsung hero who worked for the betterment of landless and bonded workers. He also formed a group of singers and folk artistes who sang bhajans of Kabir and staged performances woven with messages against exploitation

Revolutionary Comrade Durjan Singh – Life and Struggles is a short but very inspiring and interesting biography of a communist who struggled for the rights of the poorest people in the Bundelkhand Region. In view of the current weak state of the Communist parties in the Hindi belt, it may be of interest to young people that the Communist Party of India (CPI), both before and after its split, was very strong in the undivided Banda District (covering Banda and Chitrakut Districts) and would win state assembly and occasionally even Lok Sabha elections.

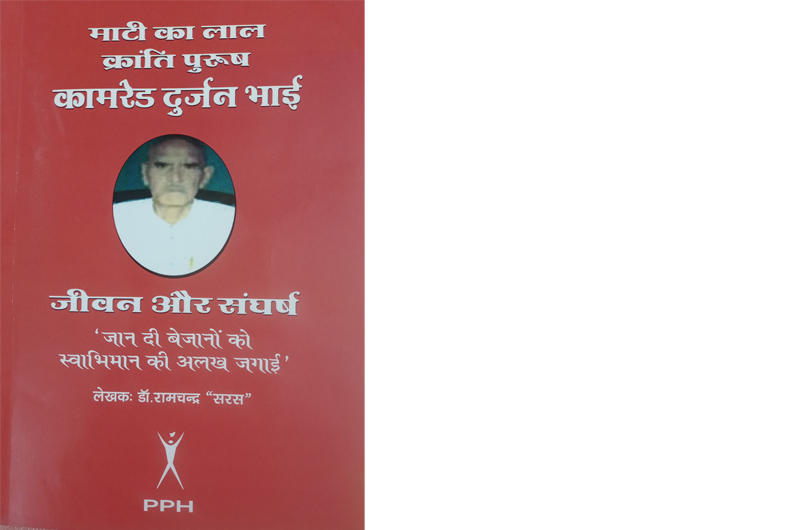

The book, written by Ram Chandra ‘Saras’ and published by People’s Publishing House, tells the life-story of one of the most courageous communist activists of those times, Durjan Singh. While several other communist leaders here came from middle- or upper-class families, Durjan Singh was a Dalit from a landless family of farm labourers. He worked as bonded or semi-bonded labour in his early days. His father had done likewise. His wife too worked in similar conditions. He experienced first-hand all the pain, suffering and humiliation borne by landless Dalit farm workers. From such conditions, Durjan Singh rose to give new hope to thousands of landless and bonded workers in Banda District and beyond.

Born in or around 1901, Durjan lost his father when he was eight. His mother brought up her two sons with great difficulty. As soon as he was able to, he went to work for a big landowner. He married, but his wife died of malnutrition when she was pregnant for the first time. His family later persuaded him to remarry and, in 1926, he married Subodhia.

The Bundelkhand Region has a rich tradition of folk song and dance, and Dalits are particularly known for these arts. Durjan was an exceptionally good singer from a young age and was specially adept at singing with a dhapli (hand-held bass producing device, similar to a drum or table). He used his talent to earn some extra money and also some fame. Despite his talent in singing and folk theatre or nutanki, Durjan was by and large limited to being a farm worker due to lack of social mobility in the rigid and oppressive socio-economic conditions. Like others of his ilk, he too had become mired in debt and was beginning to lose hope of a better future.

However, things changed dramatically. In 1936, while travelling in connection with one of his song and dance performances, Durjan met a sage named Gudri Wale Baba in Korrakanak Village. He interpreted the scriptures in such a way as to convince Durjan and some others that the true path lay in a deep commitment to serving the poor and protecting them from exploitation. The Baba asked him to bring more people willing to follow the path.

Although Durjan returned to his bonded labour, he thought about what the sage had said. When faced with a situation where most of the food grain that was due to him at harvest time was being withheld to pay his debts, he decided to escape from bonded labour with his family. The landlord went after him with goons, but when Durjan drew a sword, they turned back. He then sought shelter in his wife’s village, a Dalit hamlet. Here, Durjan formed a group of singers and folk artistes who sang bhajans of Kabir and staged performances woven with messages against exploitation. They started giving bigger performances at the ashram of Gudri Wale Baba, where large numbers of people gathered to hear their songs. That was the time when the Freedom Movement was becoming strong, and the performers contributed to spreading that message, too.

After India won Independence, Durjan went to meet B.R. Ambedkar, who encouraged him to work for the Scheduled Caste Federation. He started this work but was more drawn towards the Communist movement. So he went back to Ambedkar and sought his permission to work with the Communists, and Ambedkar readily permitted him to do so, even gifting him Rs 100. In his turn, Durjan gifted the money to his new comrades.

The biographer narrates the tale grippingly up to this point, but after this, the book becomes more of a chronicle of the growth and spread of the Communist Party in Banda District, including the problems and setbacks created by division and fragmentation. An interesting bit of information available here is that the famous Hindi poet Kedarnath Aggarwal made an important contribution in the most formative phase of the communist movement in Bundelkhand.

A tragic episode recorded in the book is the police firing on 12th July 1966, in which a large number of people were either killed or injured. There were several movements to gain control of redistributed land and also to get better terms for farm workers and reduce the burden of their debt. There were struggles also to improve drought relief work. In these struggles, not only Durjan Singh but his wife Subodhia, too, participated with great courage.

Durjan Singh became the first Dalit in the state to be elected to the assembly from a general, non-reserved constituency in 1969 – he won from Baberu. However, in subsequent elections he was defeated by narrow margins. Undaunted, heh continued to work for the poor till he finally breathed his last in 1987.

(The writer is a senior freelance journalist and author who has been associated with several social movements and initiatives. He lives in New Delhi.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux