Bharat Dogra reviews a collection of short stories translated into Hindi from the original Punjabi

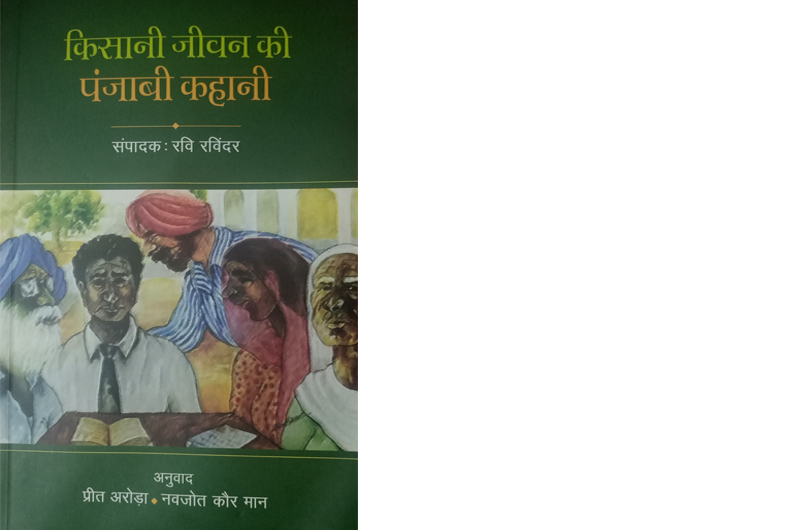

A Hindi translation of a collection of Punjabi short stories brought out by the National Book Trust presents a brilliant portrayal of socio-economic issues of farmers in the state. Kisani Jeevan Ki Punjabi Kahani (Punjabi Stories on Peasant Life), translated by Preet Arora and Navjot Kaur Mann, and edited by Ravi Ravinder, introduces the wider Hindi readership to several gems of Punjabi literature.

The book deals exclusively with stories on rural life, and is mainly about small and medium farmers, although the lives of farm workers and other sections of villagers also receive some attention. As the most prominent Green Revolution state of India, there has been much interest in the problems and prospects of Punjab’s farmers, an interest enhanced by the recent farmers’ agitation in which Punjab was prominently represented. However, in most scholarly and media discussions, the main focus was on economic issues. In this book, it is commendable that economic issues have been well integrated with social and cultural aspects, thus greatly improving understanding of contemporary and recent rural issues in the context of Punjab.

On the other hand, most of the stories are so well-written that it is the narrative and the characters which keep the reader deeply engrossed; the socio-economic understanding is an added facet. The literary merit would have reduced if the socio-economic understanding had appeared to be forced on the reader, but in most of these stories, it follows from the free-flowing narrative and the situations in which the characters find themselves; there is no need for the writers to draw any conclusions or explain the larger context.

There are 31 stories in this 482-page book and some of them are quite long. Yet, I got so absorbed in reading them that I could not leave a story unfinished even to attend to urgent work. And the memory of several characters caught in difficult and tragic situations lingers for a long time. This also demonstrates the strength of regional language writers compared to those whose medium is English. I have seldom seen such realistic portrayals from much more famous authors who write mainly in English.

Despite my great admiration for this collection, I have two reservations. There are very few, if any, women writers in this collection, although women are represented as translators. Most of the writers (although not all) have given only peripheral attention to women characters. In the context of several social issues, the reader would like to know more about the women characters.

Secondly, farm workers have also received comparatively less attention. This is particularly true of the migrant workers from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and nearby places who are referred to as bhaiyas (brothers) in these stories and are time and again mentioned in the background. No attempt has been made to understand their problems and issues or consider their perspective.

One hopes that these aspects will get more attention whenever the next edition of this book is published, with some more short stories. There are also some mistakes here and there which appear to be Hindi font related. One hopes that this too will be taken care of in the next edition.

(The writer is a senior journalist based in New Delhi. He is honorary convener, Campaign to Save Earth Now, and has authored a few books focused on the environment. His collection of Hindi short stories is available in the book, Navjivan, and of Hindi poems and songs in Ummeed Mat Chhorna.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux