Prof M.S. Swaminathan, a world scientist of rare distinction whose vision it has been to rid the world of hunger and poverty and whose work has touched the lives of millions at the grassroots in India, spoke about how “a combination of scientific skill, political will and farmer’s participation in pulses production could help achieve zero hunger”, at a programme focused on pulses for addressing food and nutrition security which was conducted at the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation. A few weeks earlier, Prof Swaminathan, despite a nagging cough, spoke to Sashi Nair, director and editor, Press Institute of India, about his life and times for the better part of an hour. Prof Swaminathan passed away today and we republish this article of October 2016 as a loving tribute to a many splendoured man

“The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much, it is whether we provide enough for those who have little.”

August 7 is the birthday of Prof M.S. Swaminathan and the Foundation Day of the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation in Taramani, Chennai. This year (2016), a selection of important publications related to agriculture, food security and policy were released by the Foundation on the day. Its founder-chairman called for the setting up of ‘seed villages’ to ensure the availability of quality seed with farmers, as well as ‘pulse panchayats’ to ensure commitment of farmers and local bodies. At 90, Prof Swaminathan, who in 1999 featured in TIME Magazine’s list of the ‘20 most influential people of the 20th Century’ (along with Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore), is as sharp as ever.

SN: Tell me about your early days in Kumbakonam. Your father was a Gandhian who influenced you, isn’t it? He ingrained a sense of service early in you?

Prof Swaminathan: My father came from a place called Monkombu in Kuttanad in Kerala. Once he got his MBBS from Madras Medical College, his professor Dr Pandalai said you go to Kumbakonam and practise, there are a lot of diseases such as filariasis, malaria, elephantiasis, etc. When I was young, I remember many individuals used to have big bloated legs there… my father was the only surgeon in Kumbakonam. He then went to Vienna to equip himself first – in those days Vienna was one of the top centres for surgeons. He returned and started a hospital with an x-ray institute where he trained his brother too. At the time it was the best hospital in Kumbakonam.

In 1936, my father died very young. He was also at the time a very strong Congressman. He was also part of the Vedaranyam Salt Stayagraha, the temple entry movement, etc. Once, he burnt the clothes he had bought from Vienna in a bonfire outside our house, for the sake of khadi. He should have been normally arrested… In the short duration of 20 years or so, he became very prominent. He adopted a two-pronged strategy to eradicate mosquitoes in Kumbakonam –education and social mobilisation. He educated people in every street where the malarial/ filarial mosquitoes were breeding. He asked them to fill up breeding grounds if they didn’t want them or spray crude oil emulsion. Within a year, the mosquitoes disappeared. He achieved this purely by making people aware.

For social mobilisation you should have some authority. So he stood for election as municipal chairman; he was unanimously elected. The municipality had 5000 or 1000 rupees, so with that… In 1933-34, Mahatma Gandhi came to our house and stayed; he used to stay in the hospital part of it. I remember Mirabehn driving us all out asking us not to trouble him. He used to collect the gold chains and ornaments and auction them. Those were early Gandhian days.

I read here (showing me the day’s newspaper) our PM asking us to Make in India. Well, khadi was the first such initiative. It taught us self-reliance, self-sufficiency and dependence on yourself. These are qualities which I might have inherited from my father, very difficult to say what I learnt and what I didn’t. Money is not important – my father would say be a trustee of your money, not the owner; use it for… purpose. He himself was very generous. His greatest achievement was in getting the Travancore temples open for Harijans.

When he died, my father’s elder brother was chief secretary to the government of Kerala (Travancore then). He was a trusted man of the Maharaja. He had somehow persuaded the Maharaja at the instance of my father to open all the temples to Harijans. The Maharaja of Travancore was thus the first to do so; in 1936 he announced all the temples in Travancore would be open to Harijans. Unfortunately, my father did not live to see it. It all went off smoothly considering that these days they are objecting to temples being opened for women and so on.

What about your move to Trivandrum and later Delhi after opting for agriculture?

After my father passed away, I went to Trivandrum for study. My uncle was there. I then had the idea of studying in Trivandrum Science College or the Maharaja’s College – first intermediate and then BSc in Zoology. At the end of my BSc, my mother wanted me to go to medical college because we had a hospital and there was nobody in the family who was a medical person. My younger brother became a pharmaceutical chemist; therefore, I applied to the medical college. But at the time, the famous Bengal Famine happened as did the Quit India Movement. It was an idealistic stage of life. I decided to go to agriculture. Kerala did not have an agricultural college. I applied to the Agriculture College in Coimbatore and joined in 1944. So I did one more BSc –this time (1944-47) in Agricultural Science. In 1947, I went to Delhi to do postgraduate work at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute.

So what really inspired you to take up agriculture?

We had a collector in Kumbakonam, S.V. Krishnaswamy, who was an ICS officer. He told me to sit for the competitive exam since there was not scope in agriculture. Since he was a highly respected figure in the family, my mother told me you do what he says. So I sat for the competitive exam, the Federal Public Service Commission at the time. Anyway, I got an offer of appointment in the Indian Police Service. I have still preserved the order. I was asked to report to Mount Abu. In those days you gave two subjects for IPS and three for IAS and IFS. I gave three but I had not prepared for anything, did not have the remotest idea of going for the civil services. My rank must have been higher for the IPS, so they must have offered. At the same time in 1949, August or September, I also got an offer from UNESCO to study in Holland – the UNESCO Government of Netherlands Fellowship. I had no idea to go to the police service or any other service, so I took advantage of the offer and went to Holland.

The Bengal Famine and Mahatma Gandhi influenced me. Even when we got freedom in 1947, although the front pages of newspapers had Jawaharlal Nehru’s famous trust with destiny speech, other pages had stories about the impending famine in India, the food shortage. We had to start the PL 480 (Public Law 480 signed by Dwight D. Eisenhower in July 1954, which created the Office of food for Peace) after waiting for a long time. Until the war (1971 war with Pakistan), we had to depend on American wheat, till Nixon stopped all that. Anyway, I thought the best way of serving the nation would be to improve food production and that too through science and technology. My idea was not to become one more farmer or one more planter. I wanted to start my work in research, develop new varieties, new technologies.

He is pictured here with Borlaug during a field visit, possibly during his years as DG, ICAR in the 1970s.

Why did you choose potato genetics?

Potato genetics, cyto-genetics or cell genetics, was the area I chose to specialise because it gave me the best opportunity to create new genetic combinations. The UNESCO Fellowship was for one year. I worked with another professor and we worked on developing a new variety of potatoes. Then I went to Cambridge (Plant Breeding Institute) for my PhD (1950-52), also on potatoes. And then on to the United States, to the University of Wisconsin. I had left India in 1949 on a small ship called Jal Azad. It was not very comfortable but being a Gandhian we had to promote all things Indian. The university (Wisconsin) was very keen that I work with them, the president even wrote me a letter saying a person of your ability should not waste time there (in India). But I returned (1954), went to Cuttack, to the Rice Research Institute. That is how my ties with Orissa began. We have a large project there, our Foundation. Then I went back to my old institution, the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), where I started work on high-yielding and semi-dwarf varieties of wheat – all well documented.

Reducing hunger and poverty has been my objective. Hunger is really triggered by poverty. Today, the sex ratio has come down in Delhi – they are attributing it to the malnutrition of mothers. In 1968, the term Green Revolution was coined. At the time I said it should be sustainable. We use too much of fertiliser. Then you have the problem of environmental degradation, yields will go down, so sustainable agriculture is important. That is why when UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) gave me an award, they called me the Father of Economic Equality in the citation. In other words, it’s all about sustainable development. And then I coined the term, Evergreen Revolution, and outlined the steps needed to move to sustainability. Conservation of biodiversity has always been one of my main thrust areas.

Why did you, between 1955 and 1972, conducted field research specially on Mexican dwarf wheat varieties?

During 1955-62, we were trying to identify varieties of wheat and rice which can respond to fertiliser application and irrigation. In the case of wheat, we found that the varieties from Japan having the Norin dwarfing genes would be able to do well under irrigated agriculture. Similarly, in the case of rice, the dwarf varieties from China could use fertiliser better. In other words, a change in plant architecture was needed and this was provided by the Mexican dwarf wheat and the subsequent wheat varieties developed by us by cross-breeding..

During 1972-79, you were director-general, Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR). This must have been something close to your heart – guiding and managing research and education in agriculture. And subsequently, as principal secretary, Ministry of Agriculture.

During 1972-79, I was DG of ICAR, when I introduced several organisational changes. The most important was the organisation of an Agriculture Research Service (ARS), which could provide, like the IAS, a kind of stability of service, ability of movement and opportunity for financial and professional advancement. I also started several other initiatives such as the Krishi Vigyan Kendra, the National Academy of Agriculture Research Management, the National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources, the National Bureau of Soil Survey and Land Use Planning, etc. Further, I established research centres in all areas where none existed before, like the Northeast Region and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. As Agriculture secretary, I developed a detailed strategy for drought management during 1978-79. It has become a model since then.

What was your focus as chairman of FAO in Rome between 1981 and 1986?

As Chairman FAO between 1981-85, I established a commission on Plant Genetic Resources. I also developed methods by which South-South collaboration could be strengthened in agriculture.

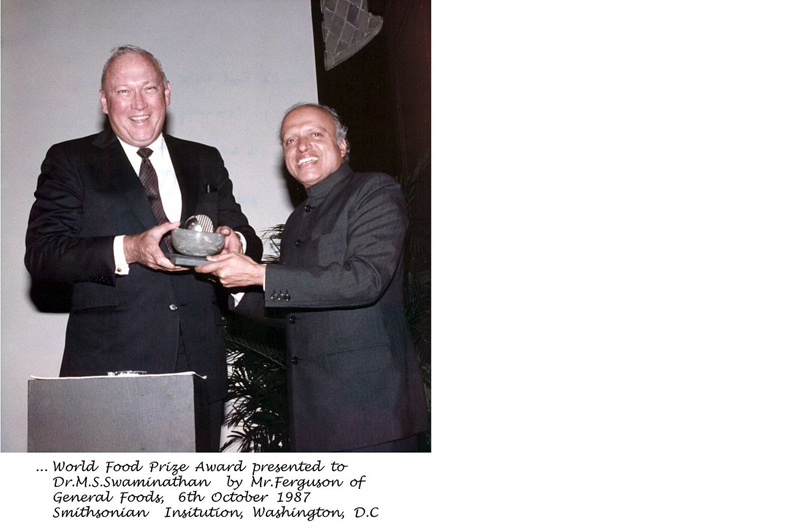

What was your reaction when you won the first World food Prize in 1987? You were then cited as “a world scientist of rare distinction”.

I was happy when I received the First World Food Prize in 1987. I mentioned at the time that the recognition was not only to me personally, but to my colleagues as well as the institutions which gave me the needed support, like IARI and ICAR.

In 1999, TIME Magazine listed you as one of 20 most influential people of the 20th Century, alongside Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore. How did you feel then at achieving such a distinction?

I always wondered how I was included along with Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore whom I worshipped. I was informed by TIME that this was on the basis of a survey made all over Asia.

You have said your vision has been to rid the world of hunger and poverty. To what extent would you say you have been successful, as far as India is concerned.

Unfortunately, a hunger-free world is still remaining a dream. I am particularly disappointed that we allowed in India the coexistence of mountains of grains and millions of hungry. Fortunately, we now have the National Food Security Act. The transition from the Bengal Famine to the ability to confer the legal right to food based on home-grown food is almost without parallel in the world

You have been an advocate of sustainable development, of environmentally sustainable agriculture, and of preservation of biodiversity. Do you see this actually happening in India?

Sustainable development involves ecologically, economically and socially sustainable growth. This will require eco-technologies and biological software for sustainable agriculture. Biodiversity conservation is exceedingly important, since biodiversity provides the feedstock for sustainability. This is why we formulated the mandate of MSSRF as “pro-nature, pro-poor and pro-woman” orientation to technology development and dissemination.

In the 21st Century, how can such battles against environmental degradation be won, do you think? What is the way forward?

The conflict between environment and development can be ended only if we can stop economic greed. Scientific skill, political will and people’s action should come together if we are to have sustainable development. The National Environmental Policy which I helped to develop 25 years ago had laid considerable stress on do-ecology, that is, to learn how to do right and not just abstain from action. No development is not sustainable development.

(Professor M.S. Swaminathan received the Padma Shri in 1967, the Padma Bhushan in 1972, and the Padma Vibhushan in 1989. He received the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1971.)

An advocate of sustainable agriculture

Mankombu Sambasivan Swaminathan, popularly known as Prof M.S. Swaminathan, passed away at his residence in Chennai today (September 28, 2023) at 11.20 am. He was 98. A plant geneticist by training, the founder chairman and chief mentor of the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai, has long been an advocate of sustainable agriculture, of the move from the ‘green’ to an ‘evergreen revolution’ to ensure food and nutrition security for all, alongside the sustainability of global food systems. He has served as chairman of the Government of India’s National Commission on Farmers, president of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, chairman of the High-Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) of the World Committee on Food Security (CFS), and member of the Indian Parliament (Rajya Sabha).

Prof Swaminathan is survived by three daughters – Dr Soumya Swaminathan, Prof Madhura Swaminathan and Prof Nitya Rao. His wife Mina Swaminathan predeceased him. Born in Kumbakonam on August 7, 1925 to Dr M.K. Sambasivan, a surgeon, and Parvati Thangammal, Swaminathan had his schooling there. His keen interest in agricultural science coupled with his father’s participation in the Freedom Movement and Mahatma Gandhi’s influence inspired him to pursue higher studies in the subject. He secured two undergraduate degrees, including one from the Agricultural College, Coimbatore (now, the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University).

(Based on a release from MSSRF)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux