In his short documentary, Tathagata Ghosh showcases the way discrimination in the name of caste, class, gender or sexuality has taken over humanity. Shoma A. Chatterji elaborates

Tathagata Ghosh is a young filmmaker honing his skills in the short film format. Strapped for funds, he tries to make do with whatever he can collect. His films have powerful agendas.

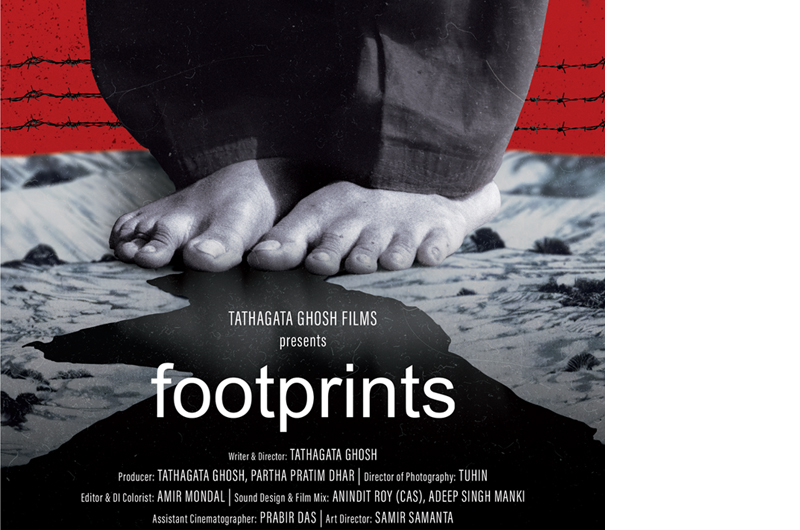

Beginning with a TV Series called Do Not Disturb in 2018, Ghosh has managed to make six short films alongside two series. His latest film, Footprints, has captured the attention of film festivals across the globe. Its running time is just 22 minutes, including the credit titles. Payel Rakshit, almost a ‘regular’ in Ghosh’s films, recently won the Critic’s Choice Best Actress Award for her work in Footprints.

Ghosh’s films, beginning with Doitto, ran successfully across film festivals in India and abroad. He began his film making and writing career after completing a diploma in Writing for Film and Television from Vancouver Film School, Canada. He worked in films and television since 2011, and subsequently decided to go ‘independent.’ He began to write, produce and direct his own films. Miss Manis about a young man who feels he is a woman trapped in a man’s body and is gay. His new film Dhulo (Scapegoat) was screened at around seven film festivals in India and beyond.

Footprints spans a single day in the life of a domestic maid who works in the posh home of a middle-class family close to the slum where she lives. An infant lying in a badly made bed in her makeshift shanty tells us she is a very young, single mother. A portrait of the girl with a man beside her gives us a hint of a partner who is no longer on the scene. It is early morning and she has to report for work. She tries to leave her baby with a neighbour but the room is locked. In another home, the couple is fighting like cats and dogs and their little son is at the door. She leaves the baby in her room and sets out to work.

Her name is Krishna – we hear it only once, when her lady boss rebukes her for reporting late for work and warns her that her pay will be cut next time. She only utters one sentence in the entire film – towards the end, when she angrily mutters to no one in particular, demanding why someone had not pulled the flush after using the toilet. It is a beautiful film simply because it is understated and subtle and nothing is said loudly.

What inspired Ghosh to make this film? “Footprints germinated from my interactions with our cook. A young lady in her early thirties and a single mother. We hardly heard her speak – she would say ‘yes’ a few times, and occasionally nod silently. But I always felt there was a strange sadness within her. And then one day, she suddenly broke down at work. After my mother and I calmed her down, she opened up to us. We saw a different side of hers. That vulnerable side made a deep impact on me. I felt guilty about how we tend to overlook certain things, even if they are right in front of us. That day, I promised to myself that I would share her story with the world. And that led me to start writing the script of Footprints. I truly feel that this film is most timely. Especially given the tough times we are living in and the increase in abuse against women and the striking growth of toxic masculinity and patriarchy. Footprints is about the women are ‘invisible’ despite being one of us.”

The family Krishna works for is a dysfunctional family where the husband and wife are forever squabbling, with the husband’s vocabulary filled with invectives. A grown daughter is forever on the phone planning to write her social work project based on their maid, while the grown son is preparing to leave for some place. Krishna discovers a packet of condoms in the husband’s trouser pocket given for washing and the wife is seated at the dining table weeping silently. The little daughter, unwanted and unloved because the father wanted a son, finds some solace from Krishna, and Krishna understands the little girl’s feeling of neglect.

The title Footprintsis a reference to the tragic reality of domestic helpers not being permitted to use the washrooms of their employers’ homes. Though Krishna feels the strong pressure to urinate, she steps into the washroom more than once but comes out without relieving herself due to fear. Unable to control her urge, she finally urinates in the compound into her salwar, tears streaking down her cheeks, and leaves her wet footprints on the floor and on the master’s trousers as she walks right over them.

“I made this film to remind myself how we often take our privileges for granted. It shocks me every day to see how discrimination in the name of caste, class, gender or sexuality has taken over humanity. I have observed all of the incidents in the film in various stages of my life, growing up in various households. I have portrayed what I have seen, and hence this film is quite personal to me. I really hope the film resonates with you,” says Ghosh.

(The writer is a senior journalist and film historian based in Kolkata.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux