There are innumerable books that have been written on Satyajit Ray, India’s best known film director in the realm of realism. Even though Ray covered a wide range of subjects such as feudalism, feminism, masculinity, oppression, poverty, love – you name it – the sensitive portrayal in each and every one of his films have left audiences world-wide mesmerised.

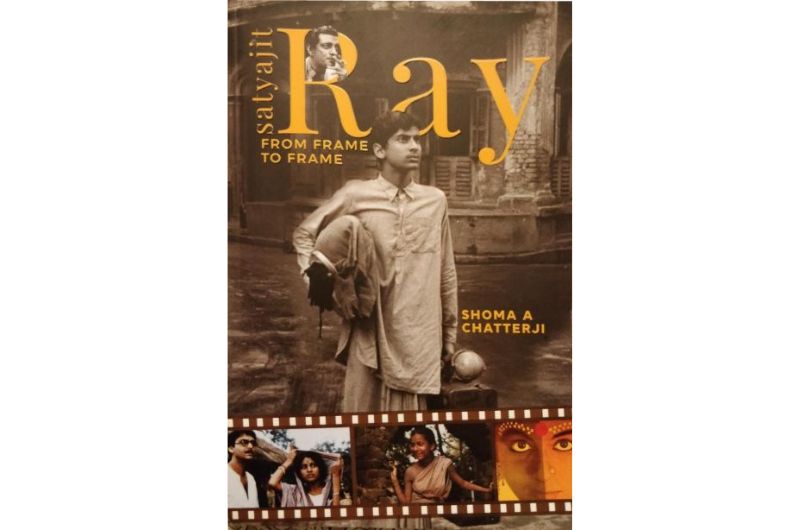

SATYAJIT RAY – FROM FRAME TO FRAME

Author: Shoma A.Chatterji

Published by: Vitasta

Price: Rs 495

Film scholar Shoma A. Chatterji, who has written on cinema extensively, with published books on Bimal Roy, Suchitra Sen, P.C. Barua among others, chooses themes that will benefit future filmmakers and scholars for the new insights she brings to the table. These help us to look at the films with a fresh perspective. For instance, she categorises the films into different themes and there is a bit of re-shuffling done here. Under the theme of poverty, she clubs not only Pather Panchali and Ashani Shanket but Goopy Gayen Bagha Bayen as well. Coming to think of it, the monda mithai cravings of two village bumpkins, which run through the film, clearly endorses the sense of rural poverty. The poverty is a nice juxtaposition with fantasy.

Similarly, masculinity as far as cowardice, escapism, vulnerability, exploitation of other weaker men and loneliness at the top are concerned and, ironically, synonymous with the male, unlike the image that is usually projected, are reflected through such gems as Pratidwandi, Sadgati and Nayak. To this list I would add Kapurush. Chatterji finds parallels with Dalit sympathies in Sadgati with Shyam Benegal’s Ankur, Prakash Jha’s Damul and even a film like Lagaan, which has a character called Kacchra.

The changing landscape both urban and rural is prevalent. The change in circumstances for an ordinary man in Parash Pathar due to a reversal in fortunes for the better questions the importance of filthy lucre and fitting into society. Chatterji has also written extensively on gender, so naturally feminism will find a pride of place in the analysis while exploring Ray’s frames. In Mahanager, we discover the metamorphosis of the housewife, the literary liaison in Charulata and the Greek tragic elements of Devi, who is worshipped as a goddess against her will.

The mainstreaming of prostitution in Seemabadha, Pratiwandi and, perhaps, even Ashani Shanket and Jana Aranya are minutely explored. Several films are left out but that is fine because Ray’s later films, due to his failing health, failed to capture the magic of his earlier films that were shot mostly outdoors – Kanchanjunga, Jalshaghar and Sonar Kella, for examples.

This is not the last book written on Ray either in English or Bengali, and film analysts will continue to find new meanings that are relevant down the ages. The different type of music for each film is classified as Shyama Sangeet in Devi, folk music in Hirak Rajar Deshe, Tagore music in Charulata and Ghair Baire – a wonderful combination – and western symphonies as and when. The reels with picture inserts on the back covers are naturally scenes of Ray’s well known films, but there is one of Dilip Kumar’s too which I could not quite place.

(Reviewed by Manjira Majumdar, independent writer and researcher who lives in Kolkata.)

July – September 2022

from Webdoux

from Webdoux