Long-held views about the role of reporters, editors and anchors or show hosts have been turned on their heads now. The changes we see have left us, the teachers of media students, perplexed when it comes to journalistic good practices, says Nagamallika G. Facts have truly become sacred, as they are rare and ephemeral, she points out

Comments are free, but facts are sacred – those were the words of C.P. Scott, editor of Manchester Guardian, in 1921, in another era. These words sound out of place in today’s media world where facts no longer seem sacred. Fact-checking has now become necessary for almost every statement made in the media. Comments are definitely being made freely ‘with malice towards one and all’ a la Khushwant Singh’s popular column. The changes we see have left us, the teachers of media students, perplexed when it comes to journalistic good practices.

One of the sacred tenets of journalism is objectivity, with both sides of the story represented and facts substantiated through independent sources. Customarily, reporters who make contacts and have authentic sources to back their stories are considered the successful ones. Legwork is held to be crucial. Even one tiny mistake is deemed unpardonable, traditionally. But these long-held views about the role of reporters, editors and anchors or show hosts have been turned on their heads now.

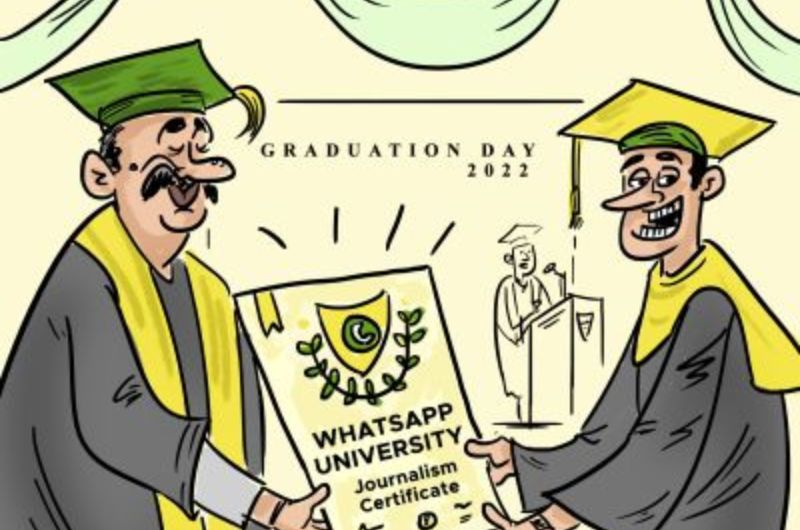

Many of today’s journalists depend solely on social media for their facts and sources – the so-called WhatsApp University that churns out ‘news, facts and figures’. With political leaders, celebrities and ordinary folk spending more time sending WhatsApp messages or re-tweeting others’ tweets without checking facts, legwork is a forgotten concept.

In the lengthy debates post demonetization, there were detailed explanations in prominent TV channels like AajTak and Zee News, regarding the 2000 rupee notes embedded with an electronic chip, which could track all your movements and unearth all the black money however deep it is hidden. This eventually turned out to be false. All that the journalists needed to have done to avoid such mistakes was to check facts with experts before airing the news.

Facts have truly become sacred, as they are rare and ephemeral. Entire websites have sprung up devoted to just checking facts. This is not to denigrate the entire media industry, as there are organisations and journalists who have responsible and society-centric programmes. The News Minute, The Scroll.in and several other media outlets speak and write about social issues that matter. Ravish Kumar, a journalist from NDTV Hindi, walks the talk, raising issues that are close to the heart of the average citizen. NDTV had a regular half-hour programme during the pandemic where the director of AIIMS and other medical professionals were asked questions and doubts that were uppermost in the minds of the common man.

The relationship between management and editors was always delicate when it came to selection of news. Clashes between the editors and owners were not uncommon. Well-known journalists like Durga Das, Frank Moraes, S. Mulgaonkar, B.G. Verghese and Kuldip Nayar were known for their editorial independence. Similarly, owners like the Jains and Birlas whose diktats prevailed over some of their editors, at times took a stand to either support or be critical of the government of the day which did not always go down well with their editors.

Some of the editors and owners did work harmoniously and were critical of the government when needed, like The Indian Express, The Statesman, The Tribune and The Telegraph. During the Emergency period (1975-77) newspapers like The Indian Express and The Statesman left their editorial pages empty as a protest against the censorship of newspapers.

The narrative today is different in most of the media, as the owners, management and the editors are often one entity. Further, many of the media owners are politicians or have affiliations to some political party or the other, like Zee TV, News 18, India TV, Sakshi TV, NewsLive, Jaya TV, Sun TV and others where the lines blur between the editorials and the government policies.

The voice of the government reverberates in television channels like Zee TV, Republic TV and Times Now, among others. Then there are those who lose out if they raise a critical voice against the government. In 2014, Manu Joseph of Open magazine was forced to resign as its editor, as his views were not considered in the recruitment of the political editor who was close to a BJP leader. Similarly, in 2018, the managing editor, Milind Khandekar, and primetime anchor Punya Prasun Bajpai of ABP News allegedly resigned after airing a news story critical of the government of the day.

Anchors or news presenters are another breed that often face the ire of the common viewers. Textbooks define anchors as mediators and moderators, not as those who sermonise through monologues. They are meant to gently lead the discussion or rather nudge it in the right direction if a debate loses its way. The prejudices or opinions of the anchor rarely have a place in such debates based on varied opinions that are offered by the experts.

Some of the broadcast media today offer examples of ‘how not to be’ an anchor rather than ‘how to be’ one. The shouting matches, deafening in decibel levels and at cross-purposes, leaves the entire debate unintelligible and toxic, serving as a propaganda tool for the media house to push ahead its ideological agenda. The number of gaffes that happen on television are not funny anymore. For instance, on one television news show, anchor Rahul Shivshankar of Times Now got the names of two experts wrong, and kept ranting for almost five minutes, insulting the wrong man. On a more serious note, a news reporter from Zee News was arrested recently for airing false news on Rahul Gandhi.

Overall, it is unfortunate that although students have the right understanding of what is healthy and not so healthy in the field of journalism, as journalists some of them are steam-rolled to fit into the overall media narrative, while others rebel or quit altogether. A few lucky ones get into media houses aligned with their interests. For media houses, influencing the policy makers may be a necessity to survive in a harsh competitive environment, but is that the ultimate goal and role of journalism and journalists? The very principles and ethics that drive journalistic are given the go-by.

The rewards, however, for us teachers, comes from those who stick to their principles, although at times the price paid is very high. Where does this leave media education? I agree that this is an oft-discussed subject, but it is not misplaced to revisit this debate in the current mediascape in India.

(The writer is professor, Department of Communication at The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad. She has nearly three decades of teaching experience in the field of Journalism and Communication.)

July – September 2022

from Webdoux

from Webdoux