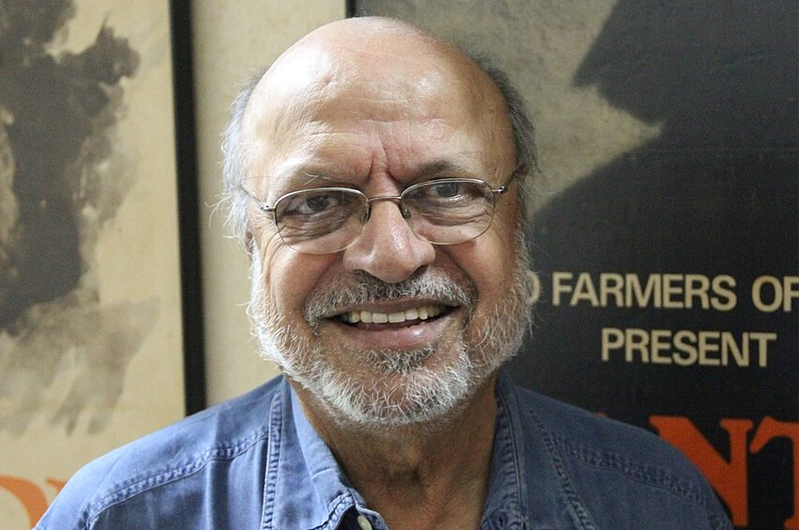

Shyam Benegal, who passed away on December 23rd 2024 soon after celebrating his 90th birthday, is considered a milestone in himself, in the history of Indian cinema. Shoma A. Chatterji pays tribute to one of the legends of Indian cinema

Shyam Benegal’s shift from making ad films under Blaze, to feature films, has, in a manner of speaking, rewritten the history of Indian cinema, consciously veering away from commercial mainstream on the one hand and completely parallel cinema on the other. The genre he pioneered, which may now be christened the ‘Shyam Benegal genre’, explored different human experiences, and often focused on the marginal, the deprived and the oppressed without raising slogans or showing candle-lit marches. He won numerous prizes, including the richly deserved Dadasaheb Phalke Award.

Benegal’s first feature film, which was funded by the Children’s Film Society of India, was shot in black-and-white and was based on Habib Tanvir’s famous play Charandas Chor. The original story was written by Vijaydan Detha. It is a scathing social satire and is about the values held by an ordinary thief who had vowed to his guru that he would remain a thief as he did not know any other work except thieving. He turns out to be a man of principles – an ‘honest’ thief with a strong sense of integrity and professional efficiency. He makes four vows to his guru – that he would never eat on a gold plate, never lead a procession in his honour, never become a king, and never marry a princess. The guru added a fifth one later – never tell a lie. As the story proceeds, one discovers that everyone else has moral lapses except him, though he is a thief. Sadly, we never get to watch a good print of the film because it is available only on YouTube channels and the quality of the print is terrible. This is perhaps the only film in which Benegal targeted a child audience.

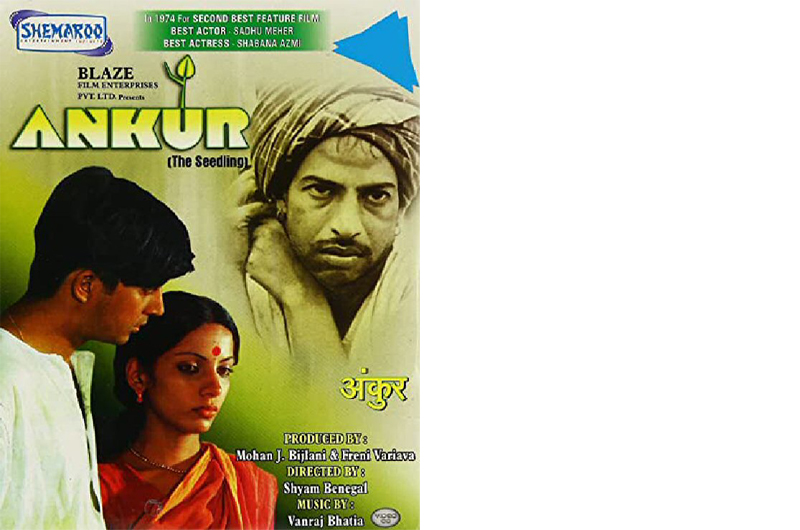

Ankur (Seedling, 1974) was almost a direct hit at the powerful landed gentry who exploited the weak. After surrendering to the sexual demands of the landlord’s son (Anant Nag), Lakshmi (Shabana Azmi) who works as a housemaid, finally rises in protest when her deaf-mute husband (Sadhu Meher), a potter and labourer, is beaten black-and-blue by the henchmen of the same landlord. The last scene – a small boy throwing a stone at the landlord’s house – encapsulates Benegal’s Left-inclined idealism.

landed gentry who exploited the weak. This poster of the film is from the writer’s archives.

Nishant (Night’s End, 1975), starring Shabana Azmi, is in some sense a continuation of Ankur. Again, sexual exploitation of women is used to bring out the evils of feudal oppression. Manthan (The Churning, 1976) was financed in the most unusual manner. Some 500,000 members of milk co-operatives in Gujarat each donated Rs 2 towards the production of the film. This was truly a people’s enterprise.A Westernised doctor sparks an uprising of the local untouchables in a village. The doctor is also attracted to a local woman, and Benegal explores the nexus between sex and power. When the film was released in Mumbai, truckloads of farmers came to watch it, and it is still part of the history of Indian cinema. In Bhumika (The Role, 1976), Benegal reveals the ambivalent attitudes of Indian society when a woman tries to live life on her own terms. The film is based on the autobiography of the Marathi actress Hansa Wadkar, essayed with eloquence by Smita Patil.

Benegal had a fondness for picking people from history and presenting little-known phases from their lives in the language of cinema. He did this in Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose – The Forgotten Hero. “I depended on the Netaji Research Bureau and other independent sources for my research for the film and now I am happy to be shooting it in Calcutta where Netaji spent some of the most significant years of his life,” he said. Benegal’s association with Netaji can be traced back to his childhood when he was introduced to the courage and the leadership potential of one of the most ignored men in the history of our country.

The Making of the Mahatma (1996) was a pleasant surprise. The Father of the Nation was portrayed as husband and father, about whom his wife Kasturba and his eldest son had many complaints. Commercially, the film flopped because the mass audience in India has for long had scant interest in Gandhi, and his image remains confined to currency notes today. However, Mujib – The Making of a Nation does not reflect the historical authenticity Benegal is known for. Part of the blame for a near-promotional tribute to Bangladesh’s Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, the assassinated and most glorified and awarded president, lies with the Ministries of Information and Broadcasting of India and Bangladesh, which co-produced the project.

Benegal made another part-biographical film called Antarnad, on the teachings and the philosophy of Guru Pandurang Shastri Athavale, but it turned out to be a washout and propagandist because the disciples of the godman produced the film. It had a very limited release.

When asked what it was about cinema as a medium of expression that attracted him, Benegal said, “Cinema uses elements practically from all the different arts – literature, painting, music, photography, dance, mime, movement and poetry. This is what attracts me to cinema. It allows you to explore all the arts while you are actually making a film, or, while you are working towards making a film.” He was not just a great master of cinema; he was an even greater human being.

(The writer is a senior freelance journalist and film historian based in Kolkata.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux