Mahmood Farooqui’s show at Shimla’s Gaiety Theatre recently was based on the 300-year-old Persian translation of The Mahabharata by Tota Ram Shayan, commissioned by Mughal Emperor Akbar. Farooqui blended Persian, Sanskrit, Arabic, Urdu and Hindi superbly to depict the powerful characters of The Mahabharata, with the focus on Karna, says Sarita Brara, as she makes a case for more such cultural shows that transcend the boundaries of religion to strengthen the unique social fabric of India

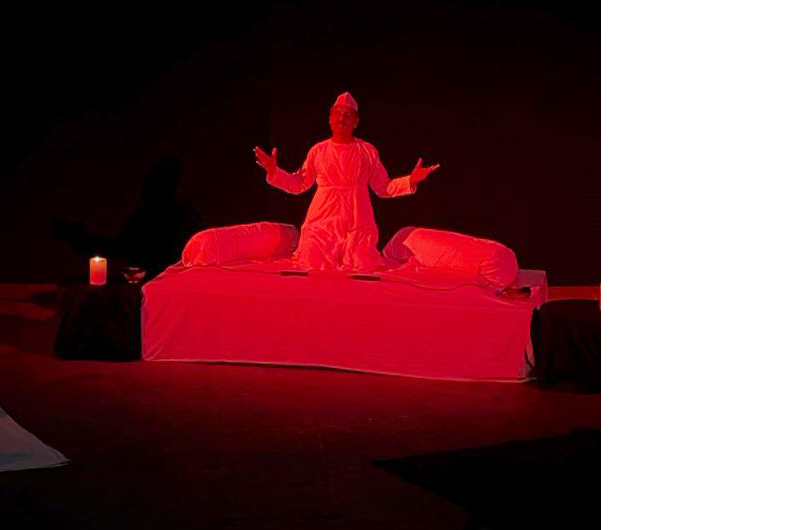

For almost two hours, Mahmood Farooqui held the audience spellbound with his mesmerising rendition of the story of Karna of The Mahabharata. He did so while sitting on the stage without moving, except to change his posture a few times. His expressions, his voice, his tone, diction and dialogue delivery matched every nuance of each of the characters that he enacted – be it Lord Krishna, Karna or any other person who forms a part of the great story. Farooqui shifted from one part of the epic to another, from one character to another, with effortless ease, in the course of his solo performance at the famous Gaiety Theatre in Shimla. The audience watched in rapt silence, rousing itself now and then to give the artiste a round of applause. And when the performance ended, Farooqui received a standing ovation that lasted several minutes.

This was for the second time that the Dastan e Karnaz Mahabharata was being performed at the Gaiety Theatre. Farooqui has staged it at the Habitat Centre, New Delhi, and at other places too. Farooqui’s show was based on the 300-year-old Persian translation of The Mahabharata by Tota Ram Shayan commissioned by Mughal Emperor Akbar. He blended Persian, Sanskrit, Arabic, Urdu and Hindi superbly to depict the powerful characters of The Mahabharata, with the focus on Karna, with his unflinching loyalty, his sense of gratitude, his unparalleled generosity, his exceptional military skillsthat matched those of Arjuna, and the angst that gripped him due to the discrimination he faced.

Made up of two Persian words, dastan and goi, Dastangoi is a storytelling tradition, referring to a storyteller. Dastans were tales of romance, of warfare and adventure, not necessarily based on real events. They were either recited or read aloud. This oral storytelling tradition was practised much before the tales were put into writing, first in Persian and then in other languages. The earliest dastan of repute is Dastan-e Amir Hamza, or Hamzanama, which is about the thrilling and fanciful adventures of Hamza, a warrior, his romantic escapades and the dangers he faced, including from supernatural beings. The mammoth Urdu version of the Hamzanama runs into 45,000 pages spanning 46 volumes.

Although dastans continued to be published into the middle of the 20th Century, their popularity started waning. In 1928, the last famous dastangoi, Mir Baqar Ali, passed away. The tradition was revived in a sense by Mahmood Farooqui in 2005. Shamsur Rehman Farooqui, a renowned writer, introduced him to Dastangoi literature. The revival saw a break from tradition, with two persons instead of a single one telling the story sometimes. Now, there are women dastangois as well.

An award-winning writer and performer, Mahmood Farooqui has written and performed nearly a dozen dastans, including on Saadat Hasan Manto, thumri singer Naina Devi, and Mir Taqi Mir, apart from the one on Karna. He was honoured with the Ramnath Goenka Award 2010 for the Best Non-fiction Work for his book Besieged Voices from Delhi 1857. In 2011, he also received the Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskar for reviving dastangoi.

The very fact that a Muslim tells the story of Karna of The Mahabharata highlights the fact that a person’s religious allegiance has got nothing to do with their artistic skills, and that no single religion has monopoly over art, literature and language. The audience at Gaiety Theatre was told how, from the time of Akbar till modern-day Pakistan, The Mahabharata has been translated into Urdu, Persian, Arabic and several other languages. Such performances can help create social harmony and need to be held more often and at as many places as possible, to prevent communal forces from attempting to divide and polarise the social fabric of our country.

(The writer is a senior journalist who divides time between New Delhi and Shimla.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux