A museum centred on the humble spinning wheel invites visitors to consider whether the country is evolving along the lines envisaged by the Father of the Nation, says Sarita Brara as she takes us on a short tour of the place

It is located right in the middle of the of Delhi’s crowded Connaught Place, buzzing with activity and, yet, once you are inside the Charkha Museum, you seem to be in another world – peace and calm descend on you, with Gandhiji occupying your thoughts. In fact, even before visitors enter the museum, a huge 25 ft x 13 ft x 8 ft charkha can be seen. The steel spinning wheel weighing 2.5 tonnes stands on a hillock overlooking Connaught Circle. It took 20 craftsmen over 72 days to create it at the Khadi Gramodyog Prayog Samiti in Ahmedabad.

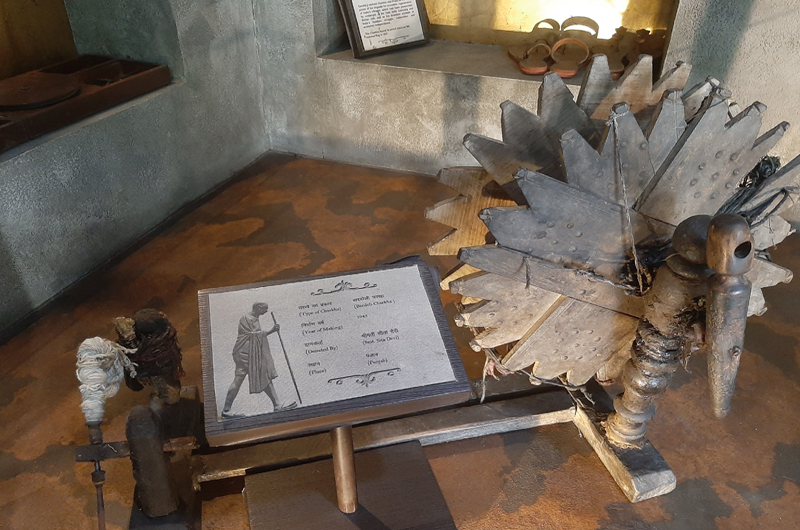

Located on Rajiv Chowk, the Charkha Museum was dedicated to the nation on 21stt May in 2017. A number of charkhas of varied types and sizes and made of different materials between 1912 and 1977 are on display at the small museum, with information about what they’re made of and when and where they were made. All the charkhas at the museum have been donated by people from across India. The museum sees a footfall of 4 000 to 5 000 on weekends and special occasions, and hundreds of people visit it on weekdays, say those who collect entrance fees at the gate.

For Gandhiji, the charkha was not just a spinning wheel, it was a symbol of sacrifice and much more. As one studies the displays at the museum, one begins to understand what the charkha meant to Gandhiji, and the associations it held for him. He saw it as poorak – complementary – to the way of life in villages, imbuing it with dignity.

“To get engrossed in the service of others is the best way to get on to know about oneself.”This is one of several quotes from Gandhiji that one reads as one walks around the museum. Another, written in Hindi and English, speaks of the India of his dreams: “I shall work for an India in which the poorest shall feel it is their country in whose making they have an effective voice, an India in which there shall be no high class and low class of people, an India in which all communities shall live in perfect harmony. There can be no room in such India for the curse of untouchability or the curse of intoxicating drinks and drugs. Women will enjoy the same right as men. We shall be at peace with all the rest of the world. This is the India of my dreams.”

There’s also an image of Mahatma Gandhi seated at the spinning wheel during a demonstration in Mizapur in Uttar Pradesh in 1925. After taking in the displays, the lawns in the complex invite one to sit down and reflect on the life and ideals of the Mahatma, who not only won India its freedom, but who practiced and taught satya and ahimsa (truth and nonviolence).

As I come out of the museum and join the milling crowds outside, I wonder whether we are living in the India of Gandhiji’s dreams.

(The writer is a senior journalist who lives in New Delhi.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux