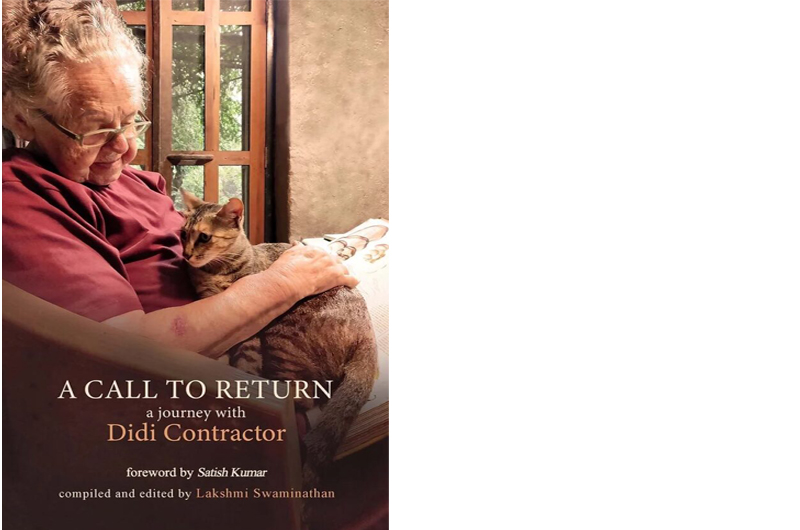

Lakshmi Swaminathan’s book, A Call to Return: A Journey with Didi Contractor, chronicles her time learning from the architect Didi Contractor, known for her ecologically sensitive architecture. Contractor’s building style emphasised the use of locally available natural materials such as mud, bamboo, and stone. She designed labour-intensive structures that utilised natural light and airflow. The book, divided into four parts, details Contractor’s life, philosophies, and work, emphasising her belief in collaboration between architects and workers and the environmental impact of buildings. This review is by Nandita Jayaraj

Having made the long journey from Chennai to Kangra, architect Lakshmi Swaminathan stepped through a porch made of stacked river stones and entered architect Didi Contractor’s humble mud-brick home. Armed with just five sets of clothes and the guileless confidence that comes with being 26, Swaminathan was eager to spend the day with the octogenarian Contractor, who was renowned for her mud, bamboo and stone-based architecture. As it turned out, she would end up spending the next four years living with and learning from Contractor, up until the latter passed away in July 2021, aged 92.

In the final years of her life, Contractor was assisted by some of her students to organise hundreds of notes and hours of audio recordings, in an attempt to document her work and philosophies. Since her death, Swaminathan continued this work and now her book, A Call to Return: A Journey with Didi Contractor, has been published. The book is 168 pages long and organised into four parts, which makes it an easy read. The first part traces Contractor’s journey to India and the turning points that led her to sustainable construction; the second part captures a glimpse of her core philosophies regarding tradition, sustainability and aesthetics. In the next part, Swaminathan compiles stories about and quotes from Contractor that depict the latter’s approach to architecture. The final part of the book comprises snippets from the numerous lectures and interactive sessions that Contractor had delivered over her career.

Didi’s journey

A Call to Return… begins with the intriguing account of how Delia Kenzinger, raised by artist parents in Europe and America, went on to meet and marry Gujarati engineer Narayan Contractor, and came to be known as Didi Contractor. For close to a decade after her marriage, Contractor lived with her husband’s traditional joint family in Nashik. Though she dabbled in various artistic and intellectual pursuits there, her professional life took off only after she moved to Mumbai. There she helped set up a school, exhibited her paintings, and eventually discovered a penchant for architecture.

But before this, she would make a name for herself as an interior decorator. Rather fortuitously, the then famous Bollywood actor Prithviraj Kapoor, happened to pass by Contractor’s self-designed family home in Juhu. He was so appreciative of what he saw that he enlisted her to work on his Juhu home and studio. She then went on to make a name for herself in interior decoration, her clients ranging from actors and filmmakers in India to a restaurant owner in Japan. In her forties, as her career was flourishing, Contractor separated from her husband, decided to pack up and moved to a remote village in Kangra Valley to begin a quieter journey, one that would see her become, in Swaminathan’s words, “a pioneer in building vernacular homes for contemporary living”.

What a building means

“Before I met Didi, I gave a lot of importance to the way the building looks,” says Swaminathan, in an interview from her small home-office in Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu. As a young student of architecture, she was drawn to the grace and the beauty of the spaces that Contractor designed – “the way she brings in light, how the light interacts with the mud walls”. With time, Swaminathan understood from Contractor that an architect also has a responsibility to consider how the space will be used once built.

For Contractor, a building was a collaboration between an architect and a worker. “We were encouraged to think like the person who is doing the actual building, how difficult or easy it is going to be for them,” recalls Swaminathan. We live in an age when every other building, whether an airport, a mall or a residential complex, claims to be ‘green’ or be ‘sustainable’. However, Didi Contractor often spoke about how any building is bound to ‘damage’ the environment to some degree, however natural be the materials and techniques used. “With each house that one builds, one is entirely changing the landscape of its immediate surroundings… No building is as beautiful, especially in this area, as the site would be without it,” the book quotes her saying.

Building styles

A Call to Return… is not a guidebook on natural building, but for readers desirous of knowing more about how Contractor used natural material in her buildings, the author has included an interesting chapter titled Building Activities. Here, she draws parallels between cities and villages, stating that in the latter, “everything has been made with affection”. While this is no doubt a somewhat romanticised view, Contractor backs it up with examples.

Contractor was a great believer in bamboo, which she recognised as abundant, less ecologically expensive than wood, and less polluting than cement and iron. She appreciated the slow setting property of mud building (“you have the time to craft”). She always tried her best to decide materials based on what was locally available; for example, rocks were broken and shaped from nearby boulders, slate was usually found in her vicinity so she would get it cut thin for use as roofs and water-resistant flooring. Contrary to the modern goal of minimising expense on labour, Contractor’s buildings were “deliberately planned to be labour-intensive and to serve as training sites for artisans”. According to her, a building was a collaboration between architect and worker. “We were encouraged to think like the person who is doing the actual building, how difficult or easy it is going to be for them,” recalls Swaminathan. She and the other interns were regularly sent off to sites to work closely with the builders.

Contractor designed homes and schools that used natural light and airflow to stay comfortable without needing much energy. Big windows, open courtyards, and verandahs brought the outdoors inside. Some of her renowned projects include the Nishtha Rural Health, Education and Environment Centre in Dharamshala, the Dharmalaya Centre for Compassionate Living in Bir, and the Sambhaavnaa Institute of Public Policy and Politics in Kandwari. She won the Nari Shakti Puraskar in 2019 for her contribution to ecologically sensitive architecture.

glass and wool. Image by Lakshmi Swaminathan.

Typically, famous architects are known for their striking and imposing structures, or their inimitable styles. Contractor, interestingly, harboured a disinclination for ‘personal style’; in fact, this was the reason she decided to not become a professional painter. Despite this, her reputation as an architect grew to a point when clients began approaching her desirous of owning a ‘Didi building’. While Contractor advocated to focus on nature, which according to her was filled with elements that are “echoing or ringing with truth”, instead of seeking out a guru or a leader, Swaminathan maintains that she sees Contractor as her guru. “A guru or a teacher is anybody who removes the darkness and shows us a way towards light. And Didi definitely has been that for me” she concludes.

There may very well be more books that emerge from Contractor and her students with the documentation efforts from her interns. For example, a book for young architects that delves into the details of Contractor’s building techniques, and perhaps a biography. A Call to Return… falls somewhere in between. Swaminathan says that the objective of this book was to communicate “Didi’s ideas and philosophies” to the people.

(Courtesy: Mongabay India/ india.mongabay.com. This article was edited by Mongabay-India’s Priyanka Shankar.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux