A doctor’s struggle to help the poorest in society has inspired a network of similar efforts in other parts of Asia. Bharat Dogra tells us the story about Dr Jack Preger

In 1972, a British doctor made sincere, but rather clumsy efforts to help with the vast medical needs of refugee camps in Bangladesh. Five decades later, this uncertain initial effort has grown to cover more than 500000 of the poorest patients, many of them with serious conditions, who would not have been able to access any care at all if not for this option. What is more, many other doctors have been inspired to make similar efforts, contributing to the spread of a street medical care movement in many countries. What is perhaps most astonishing is that this has been achieved despite so many obstructions.

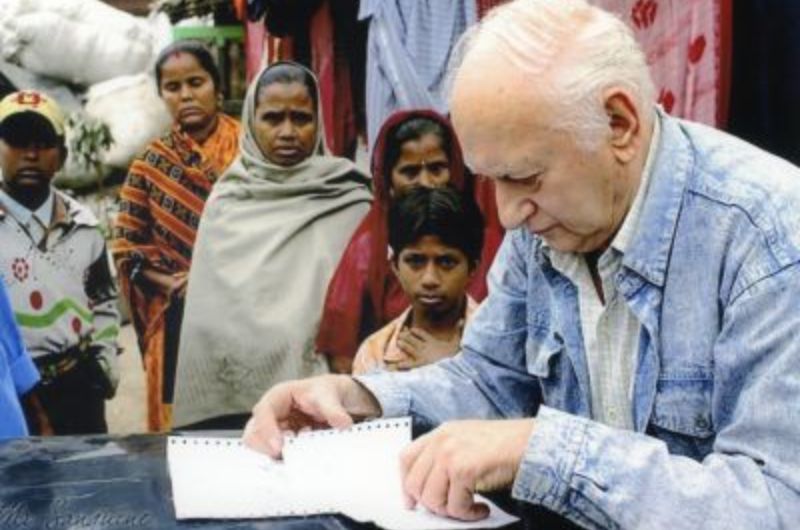

Dr Jack Preger, the unassuming man with a kind smile who started it all, graduated in Economics and Political Science from Oxford and opted to work as a farmer before responding to a call of his conscience to help the poor in distress, and enrolling at the Royal College of Surgeons, Dublin. He planned to serve in Latin America and prepared for this by learning Spanish. But, overwhelmed by news of the Bangladesh liberation struggle, he chose to travel to the newly independent country in 1972, instead, and learnt Urdu and Bangla languages.

Dr Preger started by working alone on pavements and in refugee camps. Initially, his progress was remarkable. Overcoming many difficulties, he managed to set up a clinic and then a small hospital, largely using donations from friends and sympathisers back home in UK and Europe.

But soon he came across more serious problems. He came across cases of child trafficking, involving corruption at the highest levels, and was keen to expose this.

With a keen medical eye, he explored other areas of injustice and cruelty. Several beggars appeared to have rather similar injuries, raising suspicion that they had been caused by similar means – to make them convincing in their role as beggars. However, Dr Preger’s initiatives to investigate these ills were soon brought to a rude end by officials and police, and his medical work was disrupted. He was served a deportation notice, his clinic was shut down abruptly in 1979, and patients admitted there were left to their own devices.

Though he continued to campaign against child trafficking related issues, Dr Preger decided to continue his work in India. He came to Kolkata and started anew with patients on the pavements under a flyover near the famous Howrah Bridge. The work shifted after some time to a pavement in Middleton Row, a more central part of the city, where helpers and essential provisions were more accessible. It is here that I first saw Dr Preger in action.

It was a uniquely organised medical effort on a pavement, with innovative answers being found to challenges and problems as they emerged. Medical examinations would be conducted behind hand-held bedsheets. Essential medical tests were done in nearby labs. Temporary structures of tarpaulin sheets on wooden poles provided basic protection from sun or rain. This would be dismantled every night and re-installed every morning, thus pre-empting any allegations of encroachment.

Several nearby doctors offered help and cooperation. Tourists from many countries (particularly Western ones) stopped by and several signed on as volunteers. Some of them even cancelled their existing travel pans to serve for a longer period. Nurses among them proved to be the most useful, but others helped too, for example by forming support groups in their own countries.

The clinic even helped patients in serious conditions, providing life-saving assistance with the help of several nearby hospitals. All treatment and medicines were provided free, and the poorest patients coming from longer distances even received some travel support. However, Dr Preger continued to be troubled by officials, who endlessly cited violation of one regulation or the other. He was even kept under arrest for a short while.

Despite the great uncertainty, the clinic ran without interruption for 14 years, six days a week. Finally, in 1993, government permitted formal registration of this work as Calcutta Rescue, paving the way for more clinics as well as schools and vocational training institutions. As public-spirited doctors visited Dr Preger, they felt inspired to initiate similar street medical care clinics in other places, though Jack continued to be referred to as the original pavement doctor.

In 2014, Dr Preger contributed to a network where the street doctors and other medical personnel could learn from the best practices of each other. In 2017, he became the first non-Asian to receive the Asian Philanthropy Award. In 2018-19, having set up strong systems with a dedicated team in Calcutta Rescue, he returned to the UK after completing four decades of pioneering, highly inspiring work in Kolkata – “seeking an early retirement at 88 to loaf around in Norfolk”, as he put it to me with his typical sense of humour.

And while he does that, 92-year-old Dr Preger can look back with immense satisfaction on the hundreds of thousands of people he has healed and helped back to a healthy life.

July – September 2022

from Webdoux

from Webdoux