Shoma A. Chatterji walks us through the extraordinary work of the Jeebonsmriti Archive, the brainchild of Arindam Saha Sardar

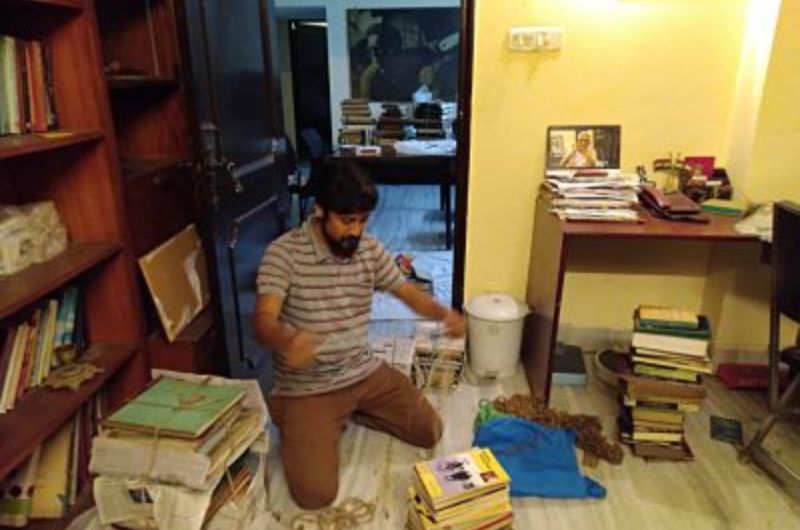

Uttarpara Bengal Photo Studio stands tucked in a corner of Uttarpara, in suburban Kolkata. It is the brainchild of 34-year-old Arindam Saha Sardar, a self-taught archivist and restoration artist. He makes biographical documentaries, curates exhibitions of rare artefacts, collects old still and movie cameras and everything he finds of archival interest.

Arindam started Bengal Studio in a rented garage in 2008. In 2010, the family relocated to Uttarpara, and Bengal Studio now has a permanent home on the ground floor of his residence. It has turned into a full-fledged digital library of music, cinema, literature, history, mythology and memorabilia of filmmakers and technicians who have either passed on or are very senior today. You’ll find old records, films, scripts, cameras donated by Soumendu Roy, Mrinal Sen and others, Buddha transcripts, ancient illustrations of the Goddess Durga, copies of old magazines and everything related to Kobi Kazi Nazrul Islam. The name of the entity has changed to Jeebonsmriti Archive.

In 2011, Uttarpara Bengal Studio held an exhibition on music, an offshoot of Arindam’s research on 78 rpm records which were brought out from 1902 to 1971. Some of the songs were played on a recorder while the portraits of music directors and vocalists of the time adorned the walls. “These 78 rpm records are original records in the Indian recording industry. Recording companies mostly stopped recording on 78 rpm from 1970,” explains Arindham.

Another earlier show was on select works of the painter-artist Nandalal Bose. An exhibition of Tagore’s sole film, Natir Pooja, was inaugurated by Tagore historian Rudraprasad Chakraborty, Amita Dutta, Tagore archivist and curator Arun Kumar Roy and Sushobhan Adhikari. In January 2013, the contribution of photographer Purnendu Bose who worked on Ray’s Sikkim was acknowledged – a first. ‘Female voices on gramophone records’ was the subject of yet another show. It included the songs of Rani Sundari, Manada Sundari, Uma Basu, Rajeshwari Dutta, Suprabha Sarkar, Sahana Devi and Bijoya Debi (Ray’s wife).

In 2014, under the auspices of the Baudhha Dharmankur Sabha, Arindham exhibited 110 digitally restored prints of paintings collected from rare magazines, books and photo albums of 19th and 20th Century on the life of Tathagata (Buddha). Also on display at Chitre Tathagata were 112 digitally restored prints of title pagesof invaluable publications in Bengali on Buddha. A similar exhibition was held in May to celebrate Buddha Purnima at Shantiniketan’s Rabindra Bhavan.

In 2015, with the cooperation of Focus, a social organisation based in Uttarpara, Arindam began work on his digital library of old Bengali magazines. The collection includes original letters handwritten by great men, diaries written by great litterateurs of Bengal and, most importantly, entire issues of old magazines like Janmabhoomi, Daasi, Bharat Barsha, Ananda Sangeet Magazine, Bangabani, Sachitra Bharat, Manasi, Mormobani, Shonibarer Chithi and others. Researchers and students can access the library.

Though he never trained in cinema, Arindham has made a few documentary films with assistance from his wife, a trained editor. The documentaries are on cinematographer Soumendu Roy and Subrata Mitra, and art director Bansi Chandragupta. His most challenging film was Bansi Chandragupta because getting material was difficult.

“While researching for my documentary on Soumendu Roy, I collected a lot of material such as entire albums of working stills of the cinematographer along with Satyajit Ray and other filmmakers like Tapan Sinha who he worked with. He gave me everything he had, such as filters, negatives, light meters and eight movie cameras including two 8mm cameras. I restored the photographs. He was overjoyed to see the quality of the restored prints. I got the idea of holding an exhibition for people interested in cinema. This led to my first exhibition of photographs on Soumendu Roy,” says Arindam, explaining how he came to be interesting in film archiving.

“I make documentaries and curate exhibitions because I never studied film or art or printing formally and this was an intensive learning process guided by Soumendu Sir; and I felt these films and related exhibitions would help people like me who cannot afford the expense of formal training to learn the techniques of filmmaking, etc,” he shares.

In Soumendu Roy and Subrata Mitra, one discovers the difference between mapping the life of a living technician on celluloid and documenting the work of a genius who is no more. The ghost-like figure of Satyajit Ray is seen hovering around the filmscapes. Subrata Mitra is more of a biographical documentary than a technical lesson in cinematography. Soumendu Roy is more a technical lesson than a biographical documentary. It is from a first-person perspective. The opening frame is mounted against a Mitchell camera which Roy began his journey with. One can hear the whirring of the reel turning as the credits come up. The film then pauses on an Arriflex, finally closing to the strains of Alo Amar Alo,areflection of the man who painted with light all his life.

The beautifully curated and orchestrated digital archive of the works of poet-musician-lyricist-actor Kazi Nazrul Islam put together by Arindam is remarkable too. “I had been researching Kazi Nazrul Islam since 2014 for a documentary on this great poet. (The film is on hold for want of funds.) I visited collectors, relatives, friends and Nazrul scholars to collect his music and songs of his. I was fortunate to get hold of the first recorded song penned by Nazrul on a 78 rpm record and sung by Harendranath Dutta. It was a political satire. That record now is a part of this digital archive,” says Arindam. He also got the original notations of Nazrul’s song compositions, a diary consisting of Nazrul’s songs written in his own hand and song booklets of three films Nazrul was involved with – Dhruba, Vidyapati and Gora.

As many as 1200 of Nazrul’s compositions between 1925 and 1950 have been restored by the young archivist. The archive includes around 500 photographs collected from different sources, some 100 rare books on Nazrul that are now out of print, 35 books of notations published from Kolkata but now out of print, and 500 songs sung by Nazrul himself. All this has been restored digitally. “We have digitalized a total of 25000 pages by taking photographs with a high-end still camera and in some cases, we have used scanners,” he says.

(The writer is a senior journalist and film historian based in Kolkata.)

October – December 2022

from Webdoux

from Webdoux