A study from rural Odisha found that exclusive focus on provision of facilities such as household latrines or bathing areas with access to piped water did not help much in improving menstrual hygiene practices until the socio-cultural barriers experienced by women were also addressed

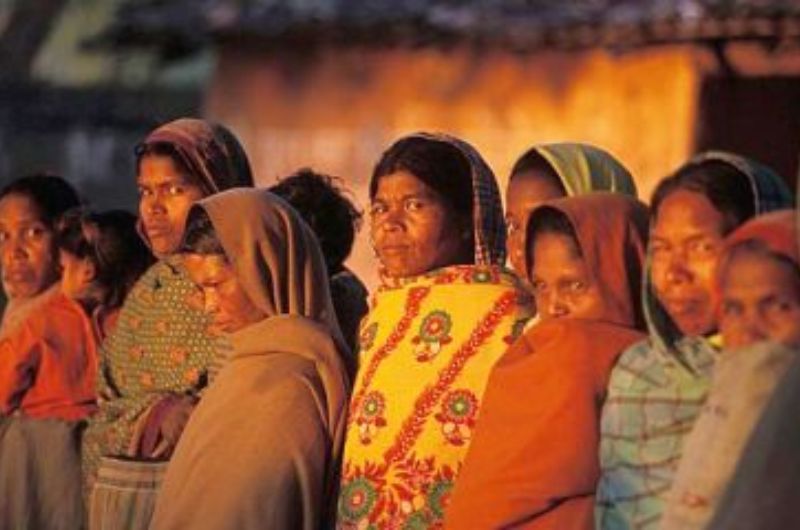

Managing menstruation, with dignity

More than 300 million girls and women between the ages of 15 and 49 are menstruating every day. Managing menstruation hygienically and with dignity is crucial for health and well being of women. The WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme on Water and Sanitation (JMP) defines menstrual hygiene management (MHM) as “Women and adolescent girls using a clean menstrual management material to absorb or collect blood that can be changed in privacy as often as necessary for the duration of the menstruation period, using soap and water for washing the body as required, and having access to facilities to dispose of used menstrual management materials”.

Access to water and sanitation, a challenge

However, according to the World Health Organisation (2019), access to household sanitation and water remains a challenge and as high as 2.3 billion people lack basic sanitation services globally, with 860 million using unimproved facilities and another 890 million practicing open defecation, and a high proportion of these reside in India.

The Government of India has made big investments in sanitation with focus on toilet construction, while fewer resources have been directed at sustained coverage and use, and little attention has been paid to women’s needs argues this paper titled ‘Effect of a combined household-level piped water and sanitation intervention on reported menstrual hygiene practices and symptoms of uro-genital infections in rural Odisha, India’ published in the International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health.

Even while rural areas may have good coverage of improved community water sources, the amount of water provided can be insufficient to maintain menstrual hygiene among women. Making adequate water available, and that too near the sanitation facilities may help to meet these needs.

Menstrual hygiene practices in rural India

The need for water is particularly urgent for menstruating women in India for personal washing and changing as a large number of women in rural areas use reusable materials that require washing. This reusable material may not be well sanitised because cleaning is often done without soap and with unclean water.

Social taboos and restrictions prevent women in rural areas from drying their menstrual clothes out in the sun and open air and they are mostly dried indoors or covered by other clothing. Unhygienic washing, drying and storing practices are common in rural areas of Odisha among women and girls from lower socio-economic groups and have been associated with urogenital infections.

Impact of WASH on MHM practices

Studies on the role of WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) in MHM have mostly looked at girls from schools and in the context of access to menstrual hygiene products. However, there is very little information on how women and girls cope with their menstrual hygiene outside the school environment and on the impact of availability of WASH on MHM practices. The paper discusses the findings of a study that assesses the impact of combined household-level piped water and sanitation interventions on MHM practices and uro-genital infection symptoms (UGS) among women from rural Odisha (India).

The study compared reproductive outcomes by conducting interviews with women from rural villages in Odisha who participated in the Gram Vikas MANTRA program, which provided household-level piped water, bathing areas and latrine (WASH facilities) to all households in intervention villages against women who did not have access to WASH facilities. The study aimed at investigating the impact of WASH intervention on menstrual hygiene management (MHM) practices; relationship between menstrual hygiene management and urogenital infections; impact of WASH intervention on uro-genital infections and determinants of adequate MHM and urogenital symptoms.

The study found that:

- Women who had access to household-level piped water, bathing areas and latrines (in the villages with WASH intervention) reported better MHM practices related to changing and washing of menstrual clothes as compared to women living in non intervention villages.

- More women living in the intervention villages changed their menstrual clothes in the household toilet and bathing room as compared to those from non intervention villages who changed their menstrual clothes outside in the fields or near a river or pond.

- Women in intervention villages washed their menstrual clothes five times more often inside the toilet or bathing room compared to women in non intervention villages.

- A fifth of women in intervention villages still used ponds to wash their menstrual clothes despite having a toilet or bathroom constructed at home. This could be explained by the socialising habits that women from rural communities have when going to open defecation, which is a rare opportunity for them to leave their houses and be free from household chores and responsibilities and talk freely to each other. Open defecation (OD) normally happens next to ponds and women probably change and wash their absorbent after practising OD. Similar practices were also found in case of bathing practices and frequency of changing menstrual clothes.

- Even though household latrines or bathing areas with access to piped water improved MHM practices, the proportion of women who practised better menstrual hygiene management practices was low (16 percent). Other factors such as type of material used or cultural and traditional habits related to changing and washing menstrual clothes influenced the behaviour of women.

- Thus while household latrines or bathing areas with access to piped water improved the environment that enabled MHM practices, the provision of such facilities alone had only a moderate impact on MHM.

- The relationship between the WASH interventions, MHM and urogenital symptoms was not very clear. Women living in the intervention villages reported less genital burning or itching compare to women living in non intervention villages. This could be because women living in non intervention villages used reusable cloth for menstrual management.

- There were several other independent factors that were found to influence MHM practices. Women who were wealthier and who had educated caregivers were more likely to have adequate MHM, suggesting the importance of knowledge and resource access.

Thus efforts to manage menstruation independently, comfortably, safely, hygienically, privately, healthily, with dignity need to look beyond facility access and focus on transformative approaches that address the gendered and socio-cultural environments that impact women.

While household piped water connections combined with community sanitation coverage is important to provide an enabling environment that leads to an improvement in MHM practices among women, devising strategies addressing other socio-cultural barriers to improve MHM is essential, argues the paper.

(Courtesy: indiawaterportal.org)

July 2022

from Webdoux

from Webdoux