As the 2024 monsoons hit the Northeastern parts of India with an intensity that communities are gradually beginning to accept, the Assam network of the Sustainable Environment and Ecological Development Society (SEEDS) was quickly checking if all 10 terra-filters that were installed in 10 locations of Cachar District of Assam in 2023 were functional and, more importantly, whether communities were able to access potable drinking water. The response from the field was delayed – due to accessibility issues. Yet, when it came, it was heartening for the team to know that all 10 were functional. This detailed report is by Sushmita Malaviya who travelled to Cachar to do the story

In the scenic Northeastern part of India, people are familiar with floods in Upper Assam where the mighty Brahmaputra flows. Lower Assam, too, experienced flooding that was destructive in 2004, 2007 and 2012. However, the Barak Valley was not prepared for the devastation that showed up in May and June 2022. In what could only be called a ‘disaster waiting to happen’, the 2022 floods in the strategically located Cachar District in southern Assam, brought life to a complete standstill as the district and adjoining areas received incessant rainfall – in two devastating spells. The first spell was in May 2022. Even before the district could assess the damage, the second spell began in June 2022.

“In the 80s when there were floods – this (was low land area) and the soil would not be washed away. The 2022 floods were devastating – everything was submerged and the soil was washed away. We went to the tila (the raised area) in a boat. The strong waves were hitting the boat as we went to the tila. The flood water was too high,” says a wizened and frail Promila Das who lives in Khelma. Nandini, who studies in Class VIII of Lakhipur Panchayat, recalls, “There is a pond near my home. In 2022, the floodwater rendered the pond unfit for bathing. There was no water supply. My father had stored potable water that lasted us for two to three weeks. That’s how we all survived.”

Learning from the 2022 floods when waters took from seven to 18 days to recede depending on which area you were in, the community-need assessments indicated that access to drinking water during floods was a major challenge for these areas. District Disaster Management Authority Programme Officer Shamim Laskar recalled that in 2022, 70 per cent of the population of Cachar District was affected. “We had no road link with the remaining part of the state or the country. After initial assessments and when relief was initiated, drinking water was what affected people were desperately searching for. SEEDS, with its experience in disaster management, was assigned the Katigorah area, in particular Gumra Gaon, Khelma, Kushiarkool and Lakhipur Panchayats, for relief and rehabilitation work.”

In the most-affected area – Katigorah – everything was underwater for over 20 days. Reports at that point showed that from Silchar to Kalain, bridges where broken, the edges of roads washed away, and deep gorges ploughed through the land that would have been washed away to let the furious waters pass. Talking to the community in four different panchayats, the animated conversations vividly brought back memories of experiences. “A litre of drinking water was selling at Rs 200 and the 10-litre jar was selling at Rs 900. Boats to evacuate people were available at Rs 10,000,” says Sarah Begum in Gumra Grant Village of Kushiarkool Panchayat.

SEEDS Partnerships and Mobilisation Director Parag Talankar was amongst the first responders on the ground in Cachar in 2022. He recalls, “Cachar was ravaged. As I navigated flooded areas, the challenges faced by residents underscored the dire need for immediate support and relief efforts.” Prior to the flooding, communities here were already living with the reality of high iron content in the water. This had been destroying the deep borings of hand-pumps. Those with small wells and engaged in fisheries found their water sources contaminated and almost dead. The water testing report from the PHE (Public Health Engineering) Department showed the water in several of the areas contained iron for which the community could not use the water for drinking both because of the foul odour as well as the brackish colour that it left on washed utensils. Assessing the situation, SEEDS proposed the setting up of terra-filters in the area.

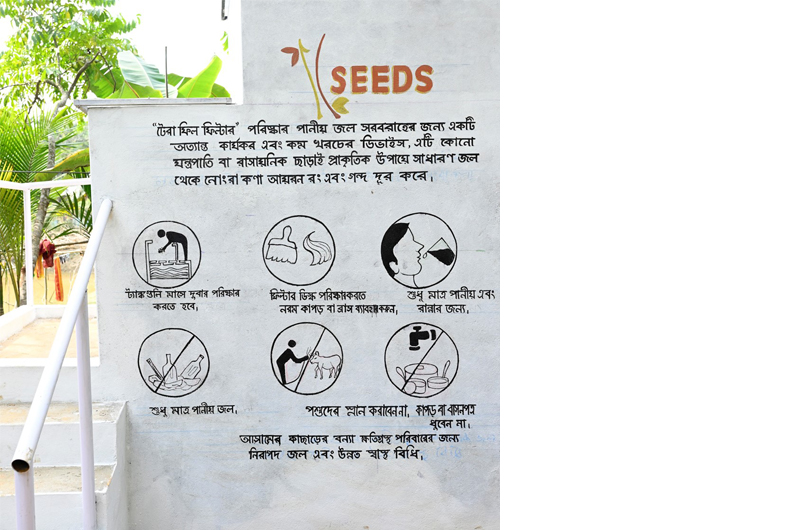

Cut to 2024, the Katigorah area in particular: Gumra Gaon, Khelma, Kushiarkool and Lakhipur Panchayats where SEEDS had intervened to support emergency relief and rehabilitation, the efforts to build back better were showing up. Even though the water level was high, drinking water was available. Since 2016, SEEDS has supported the installation of the Defence Research and Development Organisation- (DRDO) patented terra-filters in Bihar and Assam. Floods further devastate water sources leaving communities vulnerable to waterborne diseases. For a region that reports contamination and high iron content in water, post floods, the situation deteriorates further as cases of diarrhoea, dysentery and jaundice spread.

In these flood-prone areas, SEEDS is not just providing immediate relief during disasters. It is facilitating safe water for affected communities, which is a fundamental human right in disaster-affected areas. These efforts also support implementing sustainable solutions that address long-term challenges. Terra-filters address the urgent need for safe drinking water following an event of flooding. Through the rehabilitation work in 2023, SEEDS identified 10 areas in Katigorah with an existing government tube-well that were vulnerable to another flooding episode where the DRDO-patented terra-filters were installed.

of drinking water even when their areas are flooded.

In Mahadevpura, where one of the terra-filters have been installed, Shefali Chowdhury, Pratibha Rani and Soma Das eagerly point out how high the water was in the local anganwadi (nursery) centre. The floods had submerged its boundary walls. The terra-filter stands at the level of the boundary wall. With steps leading people to the sturdy platform, the terra-filter has two tanks. The topmost tank has terracotta filter disks that allow water to be filtered to a tank below. The simple logic of the tank is that if it is filled with water that filters to the tank below, during any emergency residents of the area will have access to 1000 litres of potable water.

Says Manika Das, “We had never seen a terra-filter. We now have it. We need water. If we had another one it would have been good. There are too many people and one filter will not be sufficient for all. In Khelma Gram Panchayat, Supriya Mirde explains that very often drinking water in her village is “very muddy”. In Mahadevpur, when the initial work for the terra-filters began, the community came together and kept vigilance on the materials that were coming into the village for construction work. Chowdhury, Rani and Das along with other women in the village speak about keeping the local hand-pump going and they mention that they have been informed by the ‘decision makers’ that a water filter is being built, “We are waiting to see how this helps our lives. But let me tell you when we make tea, the right colour does not show up. There is sometime amiss with the water here,” says Chowdhury.

Building back better to ensure that communities can be better equipped if there was another similar event is the foundation of SEEDS’ interventions in Cachar. Talankar, who has 15 years of disaster management experience, recalls the need assessment and the planning that was required to get communities in these areas back on track. Awareness campaigns were also taken up in the area. The first tasks that emerged were to restore and refurbish schools, and support the primary health centre with their renovation. Further, for supporting communities to be resilient, it was important to also ensure that the community ‘shelters’ were provided with solar-powered lights. Given that most of them were in low lying areas, ground-filling, too, was needed.

National Health Mission Community mobiliser Debajyoti Roy remembers, “This was inexplicable back-to-back floods. Immediate, humanitarian efforts included setting up relief efforts such as community kitchens that were critically required because people received grains but they did not have access to cooking fuels, neither gas nor firewood. For days people survived on puffed rice. With animal carcasses all around us, the goal was disease prevention. During that time, stomach ailments, skin problems and itches had to be attended to.”

The ASHAs (accredited social health activists), whose own homes were submerged, were out on boats providing community with halogen tablets[i]where ever they could find them. ASHA Shipra Das recalls that her priority was keeping track of all pregnant women. “Keeping their immunisation schedules, ensuring that girls and women had access to sanitary pads, all of this was very challenging during this difficult time,” she explains.

Says Talankar, “Although life was deeply impacted, I experienced the community’s extraordinary resilience. Their unwavering spirit to rebuild was truly inspiring. It also underscored the need to rebuild in a way that could ensure sustainable livelihoods and the need to scale them up to strengthen local risk reduction.” Roy makes a pertinent point about preparedness. “In 2004 no one was prepared. There was some preparedness in 2007. There was some build up of preparedness that the district had conducted in terms of mock drills. But the magnitude of the 2022 floods was such that we were caught off guard.”

A community volunteer Vikas Bhumij says, “SEEDS has been working in this area for several years and I have seen the bamboo shelters that they put up. The manner in which they motivative and gather community to work towards restoration is something that I learned from them. Through the trainings we learned how to keep everyone in the community safe.”

(The writer was a Charles Wallace Visiting Fellow at Cardiff University, UK, in 2001. She has worked with the Hindustan Times and Central Chronicle in Bhopal, and The Patriot and The Statesman in New Delhi. Since 2007, she has been supporting large public health programmes in India such as polio, routine immunisation, family planning, tuberculosis and nutrition. She continues to explore the relationship between environment and public health in India in her writings. The writer’s travel to Assam was facilitated by SEEDS.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux