Farmers in the semi-arid Marathwada Region are desilting local water bodies for increased water availability and higher crop yield. The Maharashtra Government has a scheme to promote desiltation activities. Farmers using the silt in their fields have reported improved crop productivity. This comprehensive report is by Nidhi Jamwal

Travelling through rural Maharashtra evokes memories of the 1972 drought, one of the worst in the state’s history, which prompted the launch of a massive water conservation programme. In response to the severe shortfall of food, fodder, and drinking water, caused by low monsoon rainfall from 1970 to 1973, the state government, with the support of villagers, constructed hundreds of water conservation structures to capture rainwater. Many of these structures were built on community lands as ‘commons’ and are managed by local communities. One such structure — an earthen dam and its 21-hectare percolation tank — is located near Borgaon Math Village in Jalna District, about 420 kilometres east of Mumbai. Jalna lies in the semi-arid Marathwada Region of Maharashtra, infamous for recurring droughts and high farmer suicide cases.

Over the years, the percolation tank in Borgaon Math had collected silt and could no longer capture and store rainwater and runoff. Recently, villagers came together to revive the water body as part of a community stewardship initiative. Not only have they desilted the tank, but they have also used the silt in their farmlands and are reporting a higher crop yield. “Our percolation tank was built way back in 1972 and had filled up with gaal [silt]. It no longer could hold any rainwater, which washed away as runoff in no time,” says Namdeo Sahebrao Kakode, secretary of Borgaon Math’s village development committee (VDC). “Two years ago, the villagers pooled their resources and desilted the tank using a JCB equipment. The farmers used the thousands of quintals of silt that came out in their fields. Our tank is now brimming with rainwater, and our crop productivity has gone up manifold,” says the secretary.

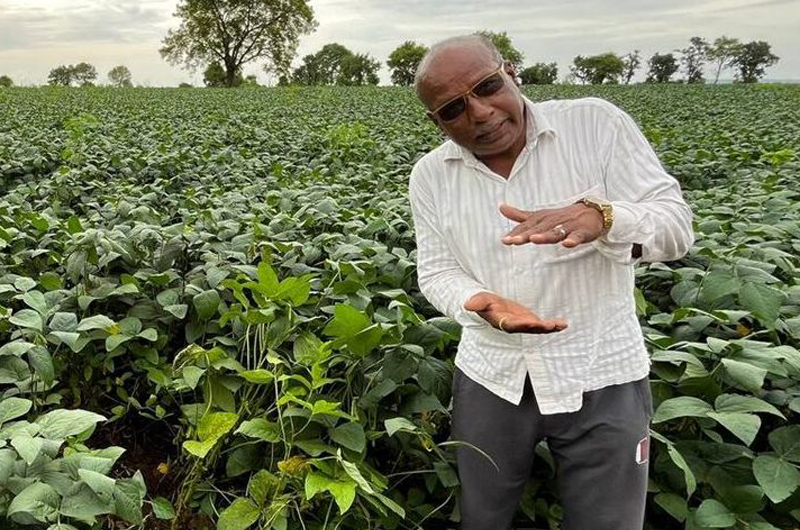

Borgaon Math has 82 households and a total agricultural land of 495 hectares. Jagan Sukhdev Joshi owns 1.6 hectares of land there. “My farmland was degraded; it had no topsoil and was filled with small stones; hence, whatever I cultivated, the yield remained low,” he tells Mongabay India. “I was part of the team that desilted our tank and I used 1,300 tractors-load of silt on my four-acre land,” says the farmer as he stands in his now waist-high soybean farm. He had to pay Rs 100 per trip of tractor to transport silt to his farm, but the expenses were worth it, he says. “Earlier, my soybean production was barely eight to ten quintals. Since applying the silt, I have been able to harvest over 40 quintals. Each quintal of soybean is sold for about Rs 4,500,” says Joshi.

About 350 kilometres southeast of Borgaon Math lies Sagroli Village in Biloli Taluka of Nanded District, also a part of the Marathwada Region. The Sagroli Village pond had almost dried up, and the groundwater, the only source of irrigation for the farmers there, had plummeted below 150 metres. Sanskriti Samvardhan Mandal, a Nanded-based NGO, and the Department of Soil and Water Conservation, Nanded, decided to rope the villagers to desilt the pond to capture the rainwater.

Around 11,000 cubic metres of silt was removed from the Sagroli pond, which the farmers used to level their farmlands. And the benefits have been immense, as recorded in a report, Back from the Brink: Rejuvenating India’s Lakes, Ponds and Tanks: A Compendium of Success Stories, released recently by a New Delhi-based think tank, Centre for Science and Environment (CSE). The report records how “the borewells near the pond became recharged. Groundwater increased by more than 100 metres. The irrigated area in the kharif and rabi seasons increased by 32 per cent and 43 per cent, respectively.”

Desilting tanks for twin benefits

The Maharashtra government has been promoting community-based tank desiltation works under its Gaalmukt Dharan, Gaalyukt Shivar Yojana (GDGS), a scheme for silt-free water reservoirs and silt-applied farms, launched in May 2017. The state has 96,033 functioning water bodies (percolation tanks) in rural areas, as noted in an October 2023 report titled Rejuvenated Water Bodies for Drought Resilience: A Look Five Years Later (2016-17 to 2020-21), jointly prepared by the Mumbai-based ATE Chandra Foundation and the Pune-based Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR).

The joint study, which covers nine percolation tanks (six ‘treated’ where water conservation works were carried out and three ‘control’) in the Beed and Nanded Districts of Marathwada, found that “the desiltation activity has resulted in a positive impact on the water spread area, vegetation cover, and gross cropped area… Availability of water for domestic purposes also saw improvements, with treated villages experiencing a 41 per cent growth from 2013-14 to 2020-21, compared to 34 per cent in control villages.” According to the report, the excavation and application of tank silt into agricultural fields affected soil texture, improved water access, and reduced dry spells compared to 2013-14 (baseline year). This resulted in increased crop productivity in silt-treated plots. “The silt-applied plots consistently outperformed non-silt plots in various villages, with net changes in crop productivity ranging from 10 per cent to 45 per cent in 2020-21 in comparison to 2013-14,” it notes.

“There is immense potential for desilting tanks in Maharashtra. This increases the availability of surface water, recharges the groundwater and leads to higher crop productivity that translates into higher income for farmers,” says Gayatri Nair Lobo, chief executive officer of ATE Chandra Foundation. “The GDGS Scheme, a government programme, brings together NGOs, CSR funds and village communities to work together to revive water bodies. In a changing climate, water stress is becoming a huge concern, and decentralised solutions are available in villages where desilting and revival of ponds/ tanks can help deal with recurring droughts due to erratic rainfall patterns,” she says.

CSE’s recent report also lists Maharashtra’s GDGS as an impactful state-level scheme. It notes that “the state’s focus on desilting water bodies is crucial, given that Maharashtra has the highest percentage of irrigation tanks (42 per cent) in India. These tanks play a vital role in agricultural irrigation, groundwater replenishment, and providing clean drinking water for livestock.” Since its launch in 2017, over 71 million cubic metres of silt has been removed from 7,504 water bodies/ reservoirs in the state, notes CSE. The GDGS Scheme was to wind up by March 2021 but has been extended, seeing its potential for sustainable water management.

In April 2023, the state government announced a subsidy of Rs 37,500 to farmers to use 400 cubic metres of silt in their fields. This subsidy aims to incentivise farmers to participate in the desiltation process, thereby improving water management and agricultural output. Purushottam Phadat of Borgaon Math Village swears by the black silt that now covers his three-acre land. “My land had no black soil, and I could not grow anything on it for five years. When we desilted our tank two years ago, I took 1,100 tractors of silt and put it over my land,” says the farmer who has planted soybean this kharif season. “Earlier, my three-acre land used to give 12-13 quintals of soybean. Since 2022, after I applied silt, my production has jumped to 38 quintals. Since my soil quality has improved, water consumption for irrigation has also come down,” says Phadat. “I spent Rs 1.80 lakh (Rs 180,000) in transporting gaal and applying on my fields, but it was worth paying,” he adds.

According to Kakode, secretary of the Borgaon Math Development Committee, before undertaking desiltation works, a series of meetings were held in the village. “We took permission from the panchayat to desilt our percolation tank. We then enlisted the support of farmers, who were ready to pitch in financially and also through manual labour to desilt our tank. WOTR also supported us in the entire exercise,” he says.

Drought-proofing by desilting tanks

Desilting of community water bodies is helping build drought resilience, claims Shyam Padulkar, WOTR’s regional manager in Aurangabad Division. For instance, Borgaon Math has 50-55 dug wells (about 50 metres deep), which farmers use for irrigating their farmlands. But, during summer months, the dug wells went dry, forcing the villagers to call for water tankers to meet their drinking water needs till the arrival of the monsoon. “But since the desilting of the percolation tank in 2021-22, dug wells have water all through the year, at least to meet the drinking water needs. Capturing rainwater in the tank has raised groundwater levels, which keep dug wells alive in the peak summer months,” explains Padulkar.

Sushmita Sengupta, senior programme manager (water programme) with CSE, says that community involvement is the key to sustainable water management at the village level. “Revival and maintenance of water bodies in rural and urban areas can help drought-proof the country and benefit the farmers in terms of increased farm output. A lot of work is already happening. For instance, temple ponds in south India are being revived through community participation,” says Sengupta, who is the lead writer of CSE’s report. “Under the GDGS Scheme of Maharashtra, water bodies have been revived, but dedicated funds and continued mass awareness are required for restoration works to be sustainable. The Central Government has launched Mission Amrit Sarovar, which is a good programme to rejuvenate water bodies, but it does not talk about funds. It is an umbrella mission that covers the water bodies under different state programmes,” she adds.

clean drinking water to households in the village.

Addressing challenges

Community-managed irrigation tanks have a huge potential to transform rural Maharashtra, as pointed out by various reports. NITI Aayog has also noted the benefits of desilting of water bodies in Maharashtra, which has increased water-holding capacity and improved organic carbon in the soil after silt application. The area under cultivation of rabi and kharif crops has reported an increase, and there has been a reduction in the per-acre cost of fertilisers and an increase in farmers’ income. However, to make a noticeable impact at the state or national level, some issues need to be addressed, according to sector experts.

A significant roadblock in the entire exercise of desilting and revival of water bodies is a lack of credible data on the actual number of water bodies in rural and urban areas of the country, says Sengupta. “In each state, or within different regions of a state, a water body has its own local name and classification — a tank, lake, pokhar, pukur, baoli, etc. These water bodies come under different authorities, and often, they are no one’s responsibility. Water bodies that are ‘commons’ are no one’s child. This needs to be addressed urgently,” she says.

India has over two million (2,424,540) water bodies, according to the country’s first census of these water resources, published in 2023. Over 97 per cent of these are located in rural areas. “But this number is an underestimation as not all water bodies have been recorded in the census. A comprehensive database of water bodies needs to be prepared and made available on a dashboard,” says Sengupta. The joint study by ATE Chandra Foundation and WOTR also points out that since these water bodies do not appear to belong to any particular group, the dumping of market waste, household garbage, and township waste is a common practice. Untreated wastewater often flows into these ponds.

“Post desiltation and revival of a water body, its maintenance and management are crucial for sustainability. That is why local villagers have to be involved as stakeholders and their contribution is important,” says Lobo. “We have found that through farmers’ participation, the standard operating rate of desilting activities comes down from Rs 120-200 per cubic metre to Rs 30-35 per cubic metre. Tank committees need to be formed for governance and management of desilted percolation tanks,” she adds.

It is essential that water is judiciously, efficiently, and equitably used and the quality of the resource (water body) is protected in order to mitigate climate risks. The gram panchayat or a water user association can be mandated and its capacities built to assume “stewardship of the water body,” recommends the joint report by ATE Chandra Foundation and WOTR. “Once a water body is revived and water becomes available, extra care has to be provided so that the marginalised and vulnerable communities in the village also benefit from it. Often, poor families cannot afford transportation costs of silt to their farmlands and need financial support,” says Padulkar.

(Courtesy: Mongabay India/ india.mongabay.com. This story is supported by the Promise of Commons Media Fellowship 2024, focusing on the significance of commons and its community stewardship.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux