Suvobrata Ganguly profiles an enterprise that was started as a cottage industry by two freedom fighters to make desi (Indian) ink for the Father of the Nation, then gained immense traction, fell off the grid, and is now back in the reckoning. This is not only a fascinating story about the past but also about how, in recent years, Sulekha visited schools and encouraged students to take up writing with fountain pen and ink, and how it created a compelling narrative around the brand, often collaborating with artists and letting them use the packaging as canvases to highlight their creativity. Incidentally, Sulekha’s factory runs on clean energy, with a zero carbon footprint. It is an equal opportunity employer

Is Gandhi still relevant? What about his teachings, the core values that he wanted a generation to imbibe? Is the product itself an anachronism? Buckle up, for I am going to relate a fascinating story – a story of Sulekha Inks, and its phoenix act far from the glare of publicity. But first, the backgrounder…

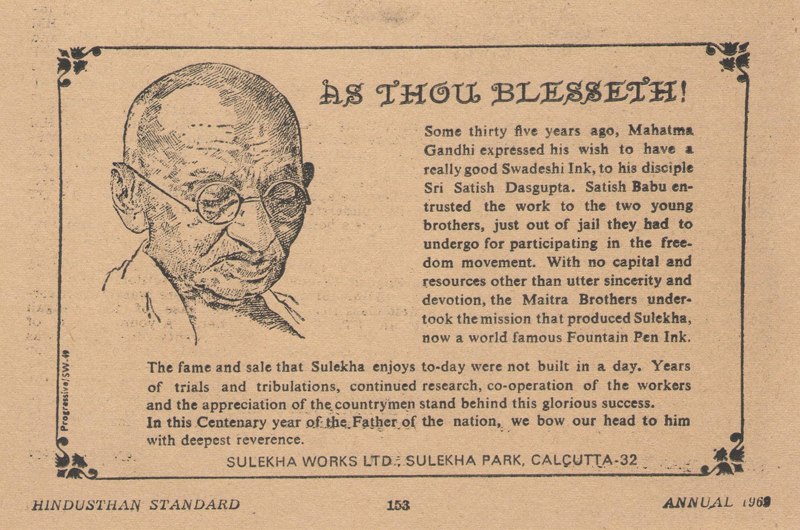

Sulekha was started by two Gandhian freedom fighters – brothers Shankaracharya and Nanigopal Maitra – in Rajshahi (now in Bangladesh). The year was 1934. And their mission was simple – to make swadeshi (home-made/ Indian – The Swadeshi Movement was a self-sufficiency movement that was part of the struggle for India’s Independence) inks for Gandhiji to write with, as he had expressed his displeasure about using imported inks on multiple occasions.

The Maitra brothers’ father donated his life’s savings and their mother her jewels, for Sulekha to make the inks for the Father of the Nation, Mahatma Gandhi. Initially, Nanigopal, a science graduate, dedicated himself to perfecting the original formula for ink made by noted Gandhian Satish Chandra Dasgupta, a retired chemist of Bengal Chemicals, another swadeshi enterprise. Nanigopal’s aim was to make the Sulekha ink comparable to the best in the world. The women of the house made the ink according to this formula, and Shankaracharya Maitra ferried it on his cycle to buyers and khadi shops through which they were primarily marketed.

donated his life’s savings and their mother her jewels, for Sulekha to make the inks for Mahatma Gandhi.

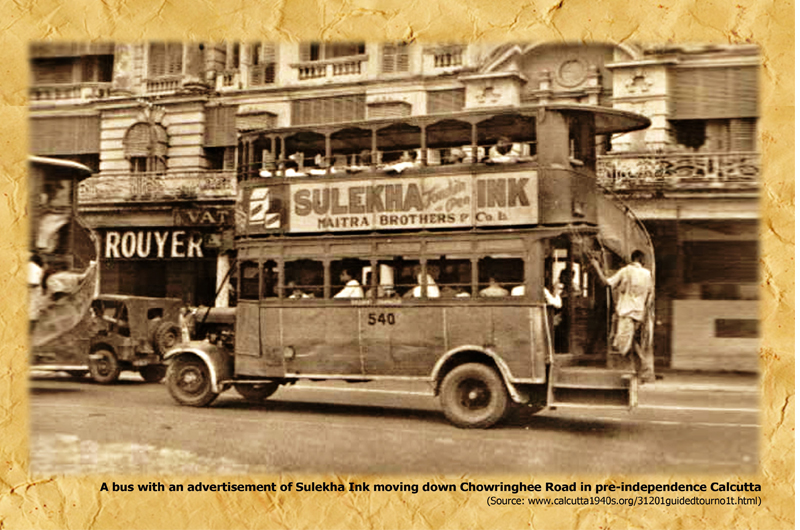

From these humble origins to how Sulekha relocated to Calcutta and gradually became ‘ink makers to the nation’, despite the trials and tribulations it had to face post-Independence, is a story that has been told on numerous occasions, and I will desist from going into it. Suffice it to say, not only was it the largest swadeshi brand in its segment, it also had a pan-India footprint, with a near 90 per cent market share in eastern India and exports to all corners of the globe. In the mid-1980s, Sulekha bid and won, in the face of stiff global competition, a contract to set up Africa’s first ink factory in Kenya, which it did with distinction.

However, the influx of refugees post-Partition and again before the Bangladesh War in 1971, created a strain on the resources of the entity, as the owners, true to the Gandhian spirit that they lived by, went out of their way to help the uprooted people who sought refuge on this side of the fence. The Gandhian spirit also came into play when they refused to bow to the politically motivated, unjust demands of the powers then, leading to the suspension of operations in the late 1980s.

Kaushik Maitra, managing director of Sulekha (Sulekha Works Limited) now, is the grandson of the founders. An engineer by profession, he came back from the world of academia in North America to pull the company back from liquidation. Naturally, it was way easier said than done. It was lockdown time, the company had no capital to fall back on, and the product – fountain pen ink – was competing with ballpoint pens, ‘gel pens’ and digital devices that have all but pushed the traditional pen over the edge.

The more Kaushik Maitra dug his heels in to face the seemingly insurmountable obstacles, the more he realised why what he had set out to do must be done. Carelessly discarded use-and-throw ballpoint pens were creating havoc with the environment. Children were increasingly being sucked into a digital void as they tapped and typed away. The very act of handwriting was being pushed towards oblivion. As a consequence, attention spans were shrinking, the ability to retain knowledge was dwindling, and several ailments, from psychosomatic to orthopedic, like finger arthritis, were on the rise.

Sulekha diverted its scarce resources from setting up distribution channels, even from actual sales, to go to schools and encourage students to take up writing with fountain pen and ink. The response from parents and teachers was overwhelming, not to mention from the children themselves, many of whom were using a fountain pen for the first time in their lives. The nostalgia – the excitement of discovering something straight from one’s childhood – also brought many customers back into the fold, as did the exhilaration of embracing a swadeshi brand.

(Home-made) – reflecting a time when Indian freedom fighters staked their all to shake off the foreign yoke, a time when even a bottle of

swadeshi ink was a symbol of defiance.

Selling inks is no child’s play, especially in these days of short attention spans and instant gratification. This led Sulekha to create a compelling narrative around the brand and every bottle of ink it sought to market, often collaborating with artists and letting them use the packaging as canvases to highlight their creativity. As a matter of fact, such has been the impact of the move, the genre of pen-and-ink art is again gaining popularity, with some of India’s top artists embracing it.

Mention should also be made of Sulekha’s lines – Swadhin (Free), Samarpan (Dedication), Swaraj (Self-rule) and Swadeshi (Home-made) – all of which seek to go beyond the mundane and tell tales of a time when our forefathers staked their all to shake off the foreign yoke, a time when even a bottle of swadeshi ink was a symbol of defiance against an empire on which the sun seemingly never set. They also celebrate greatness, like inks dedicated to Swami Vivekananda, Mother Teresa, Jamini Roy, the Mother Tongue, and Satyajit Ray. The latest in this line was launched at the Chennai Pen Show earlier this year, a tribute to arguably the world’s greatest mathematician, Srinivasa Ramanujan.

“We may not have become a hugely successful enterprise materialistically,” says Kaushik Maitra, “but we are proud not only to walk the path shown by Gandhiji and which our forefathers trod, but to be fighting a battle to spread the values that they espoused, reliving a legacy. Our entire factory runs on clean energy – we are an entity with a zero carbon footprint. We are an equal opportunity employer, a sustainable producer, and are socially integrated. Yes, the sales are showing an upward trend. Yes, there are enquiries from around the world. Yes, we are spearheading the movement to bring back the fountain pen, ink and handwriting. But our greatest achievement is the fact that we are proving with every step we take that it is remains possible to be Gandhian in thought, belief and action, and still be successful. To me, that is a feeling that is priceless.”

(The writer, better known as Chawm Ganguly, calls himself a fountain pen and ink evangelist. A collector, historian and a raconteur, he has been working tirelessly to popularise the use of fountain pens, inks and writing, especially among the young. He is known for turning around a legacy ink brand from India. He writes a blog called Inked Happiness and creates videos on pens, inks and accessories on his YouTube channel.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux