Ranjita Biswas outlines three outstanding Indian films where nature is as much a character as the actors themselves, and the settings blend into the lives of the protagonists. The natural settings or backdrops meld with the lives of protagonists, something that’s hardly witnessed in mainstream Indian cinema today, she says, after watching a few regional language films by acclaimed directors. The landscapes depicted in the films establish how humans are shaped by the surroundings too, not by genes alone

A green landscape, a serene sea, an expanse of paddy fields stretching to the horizon – that’s the canvas against which characters come alive in some of the best films in contemporary regional cinema. These backdrops meld with the lives of protagonists, something that’s hardly witnessed in mainstream Indian cinema today, full of hyperbolic shots courtesy ‘action masters’ from abroad, choreographed songs in some exotic locales and, frankly, mostly peopled by unauthentic characters. Of course, the big budget ones boast of hundred crore business within a week of release. The fact is, the audience also laps it up, as if these are the dream worlds where they want to roam, or escape into for a few hours, which is understandable as they have to negotiate the labyrinthine lanes of daily living.

So where are the people who live in villages and eke out a living, tilling the land, getting marooned in annual floods, facing the challenges thrown by man and nature? Watching a few regional language films by acclaimed directors is like a fresh breath of air, a whiff of the earth itself.

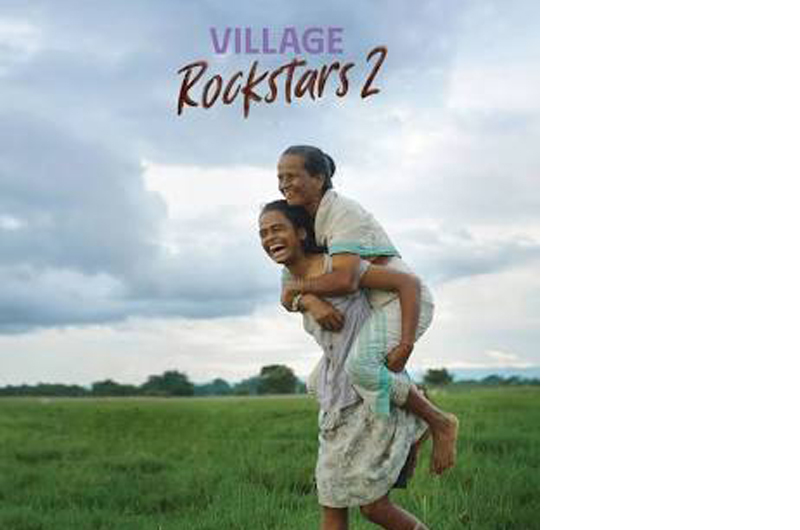

Take, for example, Assamese filmmaker Rima Das’s Village Rockstars 2, sequel to her earlier film of the same name. Despite extreme poverty, protagonist Dhunu, now a teenager, still dreams of becoming a rock star while strumming her guitar in the unlikely locale of a backward village. She and a few friends even form a band that aspires to perform at ‘town functions’ but are often shooed off. Her father is dead; her strong-willed mother somehow manages to provide two meals a day. Dhunu helps her mother as much as she can; their bonding is beautiful to watch. Her elder brother falls into bad company, but her mother still refuses to sell her plot of land to a promoter despite her son’s nudge. “This is all we have; I don’t want to be uprooted,” she says.

and thoughts that get compressed in the incessant chase of livelihood in a large city.

Yet, life is also beautiful for Dhunu, running around with friends in the fields, strumming her guitar under a tree, going fishing. The annual floods come with the inevitable temporary displacement. But, eventually, the waters recede and the fertile land becomes green and later golden brown with paddy, in an eternal cycle of nature. Her mother dies, wasting away, but Dhunu picks up the threads from the nadir of sorrow. Her brother returns to the fold as he misses his mother. The siblings bond, perhaps to face the future together. Will Dhunu become a rock star, after all? Who knows? In this heartwarming story, nature seems to become a part of the story. The verdant green fields, the distant hills, the beels where the villagers fish at night with flames on bamboo poles, the children playing in the bare fields after harvest, give a glimpse of a world that seems far away from the city lights.

A similar countryside comes alive in Sanjeev Sivan’s Malayalam film Quiet Flows the Dead (Ozhuki Ozhuki Ozhuki). Set in Kerala’s backwaters, the story is about 12-year-old Paakaran, son of a single mother, and the community’s errand boy. He cheerfully helps everyone and doesn’t have time to go to school. His mother works in a prawn factory. Paakaran is obsessed with his father’s disappearance while fishing. When he discovers a corpse floating in water while he goes fishing, he quietly retrieves it at night and gives it a proper cremation because he believes, as the priest says, the unhappy soul of an unclaimed body without burial could be roaming around. Perhaps his father had the same fate. After all, as the film’s tagline says, ‘Thousands of bodies of the unidentified dead flow in the world’s waters, far from home, as their loved ones await their return or at least a chance at a final goodbye’.

But the act lands Paakaran in trouble with the police, and even leads to a murder charge, and only the intervention of a kind police officer saves him. He is now ready to leave his beloved home and loving community for a school in the town, with the police officer’s help. Here, too, Paakaran’s story is as much about himself as of the community shaped by the backwaters in Kerala’s exquisite countryside.

rock star while strumming her guitar in the unlikely locale of a backward village. The verdant green

fields, the distant hills, the beels where the villagers fish at night with flames on bamboo poles, the

children playing in the bare fields after harvest, give a glimpse of a world that seems far away from

the city lights.

Payal Kapadia’s Cannes Grand Prix winner All We Imagine as Lightbegins with scenes of suffocating, crowded Mumbai lanes where two women from Kerala working as nurses bond in their shared apartment; but it’s only when they go back to the state to help relocate an old woman, a cook at the nursing home where they work, that they find the respite to look inward. Sitting at a ‘restaurant’, an euphemism for a shack on the sands, on a moonlit night they churn out the sensitivities of relationships and thoughts that got compressed in the incessant chase of a livelihood in the big city.

Tamil film Angammal by Vipin Radhakrishnan, based on a short story by Perumal Murugan, is about a fiery village woman who refuses to wear a blouse and wants to show off the tattoos on her arms. Problems arise when her city-educated doctor-son forms a liaison with a girl from the city. When her parents are scheduled to visit his home for a ‘discussion’, he is mortified that his mother doesn’t wear a blouse and fears he will lose face in front of his prospective in-laws. This leads to friction in the family, but Angammal is adamant. She has always followed her own counsel – she drives a motorcycle to supply milk and home-grown produce to other households. What catches the eye, besides the excellent acting, is the rural location beside a hill, its red earth a symbol of Angammal’s strong character.

Man and nature, so close for centuries, are losing out in this era of rapid ‘development’. The landscapes depicted in these films once again establish how humans are shaped by the surroundings too, not by genes alone.

(The writer is a senor journalist, translator of fiction from Assamese, and author of a coffee-table book, Brahmaputra and the Assam Valley. She is an award-winning writer of fiction for children. She lives in Kolkata.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux