How to revive indigenous rice varieties that have almost disappeared from the paddy fields of India was a subject that was given much attention at a recent conference organised by the West Bengal Biodiversity Board to commemorate Biodiversity Day (May 22). Ranjita Biswas, who attended the event, says reviving traditional species of paddy is not only important as a guarantee in the face of erratic climate conditions but also from the point of view of bio-diversity. Here is her report

Many agricultural scientists today admit that the Green Revolution (1960-70), perhaps necessary at the time to tackle food shortage, also brought in monoculture of crops, sidelining traditional varieties of rice which are better equipped to survive droughts, floods, etc, than hybrid varieties. Before the Green Revolution, a total of 1,10,000 native varieties of rice were cultivated in India, according to well-known rice scientist R. H. Richharia. In undivided Bengal in the 1940s, an astonishing 15,000 rice varieties were cultivated. In the 1970s, that number had dipped to 5,556 (Bangladesh recorded 12,479 as per the Bangladesh Rice Institute). Today, only 140 indigenous varieties of paddy remain in West Bengal. Across India, 10 high-yielding varieties rule the roost.

However, in the past decade or so, a kind of quiet revolution is taking place in Bengal’s rural areas – some traditional paddy varieties are being revived. Even tech-savvy, urban youth are taking up rice cultivation and encouraging local farmers to adopt organic farming. The government is lending a hand, too.

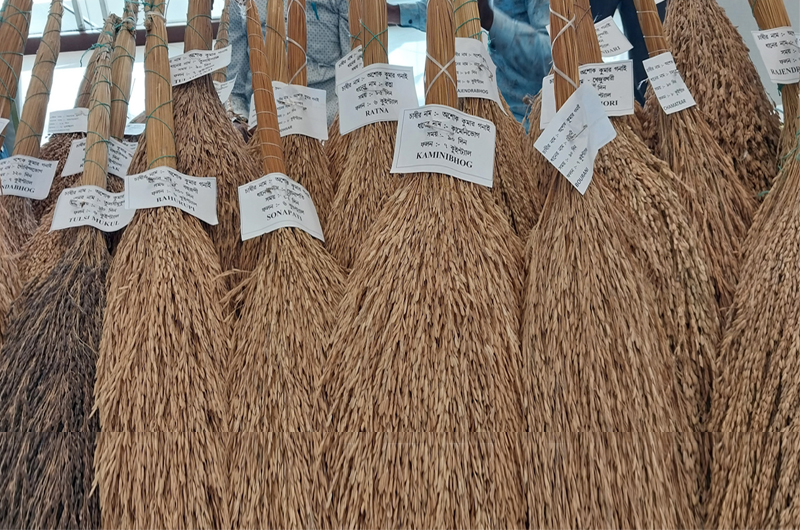

On the sidelines of the a recent conference organised by the West Bengal Biodiversity Board to commemorate Biodiversity Day (May 22), some NGOs from the hinterland displayed and offered indigenous paddy varieties for sale. Tulsi Mukul, Lal Dudheswar and Kamini Bhog were among the varieties which attracted buyers.

Observing the trend, commercial establishments market them under brand names.

India is the world’s second highest producer of rice next to China. It is the staple food of 65 per cent of its population. Yet, the general view is that rice varieties do not have enough nutrients. There is also a push from certain sections to introduce fortified rice. Debal Deb, ecologist and conservation biologist, refutes this: “A considerably large number of traditional rice varieties do contain a range of micronutrients – Vitamin B, Vitamin A and minerals. In fact, lab tests have shown that 68 local varieties contain higher levels of iron and zinc than that reported for any GM-fortified rice ever published.” He feels that there is a paucity of research in mainstream institutions to explore the nutritional profiles of indigenous rice varieties.

Deb has been collecting indigenous rice stalks for years for his Basudha Seed Bank, which now has hundreds of rice seed varieties. He has identified 15 native types that offer better produce than high-yielding seeds do in optimum conditions, and without the need for chemical fertilisers either. He does not sell the seeds but exchanges them for others with willing farmers. “Tulsi Mukul is an old rice variety of rice from Bengal and is aromatic. However, Dudheswar is now lost to farmers due to cross-pollination; as the name dudh (milk) suggests, it is pearl white. The Lal Dudheswaris a hybrid,” he explains.

There are other aromatic varieties in Bengal such as Radhatilak, Kalonunia, Karpurkanti, Gobindobhog, Chiniatope, and Badshahbhog, which were used for making payesh (rice pudding), a must for any auspicious occasion in a Bengali home – from annaprasan (first rice-eating ceremony for a child) to bhog offering at pujas. But most people today are only familiar with the Gobindobhog variety widely available in the market.

These days, the health-conscious prefer brown rice. Observing the trend, commercial establishments market them under brand names. But the traditional householders and farmers always knew that strains of unpolished brown rice like Bhadoi, Kabiraj Sal, Shatiaand Agniban, are rich in iron and antioxidants. Bhadoi is particularly prescribed for expectant mothers and anaemic patients. Kabiraj Sal, on the other hand, gives strength and is advised for convalescent patients.

The small-grained rice, Bhutmuri (ideal for making muri or puffed rice), Kelas and Kakri, PariandZinni,do not require much water and are planted on highlands. A unique rice variety called Gamrah (a native of the Kosi River bank in Bihar) is both flood- and drought-tolerant. New-age farmers are exploring these varieties. Bhairav Saini, trained under Deb, leads a cluster of farmers growing 50 traditional Bengal rice varieties of through organic farming in Bankura District.

due to cross-pollination, says an expert.

Natural disasters sometimes, ironically, make people fall back on native knowledge, as it happened with rice cultivation in Bengal. The devastating Aila Cyclone in 2009 flooded the Sundarbans Delta Region with saline water and made it unsuitable for hybrid rice cultivation. Old-timers then talked about saline-water-resistant rice varieties which had existed earlier. With natural disasters becoming more frequent due to climate change, as illustrated later by the Amphan Cyclone in 2020 and Yaas in 2021, the urgency to find a solution gathered momentum.

Nilanjan Mishra, founder of Patharpratima Runners, an organisation for cultivation and seed conservation in the Sundarbans area, talks about Malavati paddy, one of the sturdiest varieties that can withstand gusty winds and flooding of fields during the monsoon rains. Nangalmura is another sturdy variety that gives a good yield even under the most inhospitable environmental conditions.

Currently, agro-scientists in Bengal have developed around 12 to 16 salinity-resistant paddy varieties, including Nona Swarna (saline gold). The government took up the project through which salt-tolerant seeds, produced from traditional varieties and stored in government research institutes, were distributed. Initially, farmers did not have the technology or knowhow to produce salt-tolerant paddy. Awareness programmes were held via live phone-in, television, and radio talks. All these developments prove that exploring cultivation of indigenous rice varieties will not only save farmers from erratic climate conditions but will also help preserve bio-diversity.

(The writer is a veteran journalist who lives in Kolkata.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux