Alam Ara, the first Indian talkie was released on 14th March 1931. Produced and directed by Ardeshir Irani, the film performed well at the box office. Mrinal Chatterjee takes us down memory lane, describing the making of the landmark film and tells us how it also impacted the core and contours of Indian cinema. Alam-Ara, he says, was not just a film, it was a movement that transformed Indian cinema and remains a symbol of innovation, resilience, artistic evolution and the multi-cultural ecosphere of the film industry

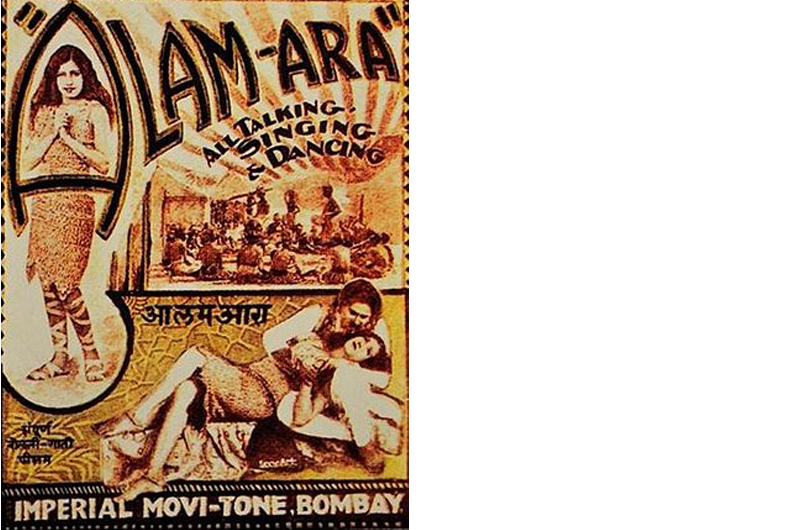

‘All living, breathing, 100% talking!’, ‘India’s first perfect talkie’ Alam Ara(Ornament of The World) – was released on 14th March 1931 at the Majestic Theatre in Bombay to a tumultuous reception. Revolutionary in the technology used and in its storytelling, language and casting, Alam Arawas a trailblazer that shaped Hindi cinema for decades. Made at a time when the Indian market was dominated by American films, its huge success led not just to the birth of the talkie in the Subcontinent, but also to several other innovations. The film was produced and directed by Ardeshir Irani (1886-1969), whose life story is as fascinating as the films he made.

Born in an immigrant Iranian-Zoroastrian family in Pune, Irani had tried his hand at being a teacher, a kerosene inspector and a seller of musical instruments. As author, filmmaker, columnist Nilosree Biswas writes, “Life changed when he (Irani) met Abduallay Esoofally, a touring cinema operator. Esoofally’s troupe travelled across the Subcontinent, showing films in tents pitched in open grounds. Colloquially known as tambu filim or tent cinemas, the shows initiated a new visual culture. When Esoofally decided to be based in Bombay and Irani became the representative of Universal Studios, Hollywood, they got into a working partnership. Together, they bought Alexandra Theatre (located in Kamathipura), gave it a face lift, and relaunched it in 1918.

Alexandra became one of the earliest single-screen theatres of South Asia and it was here that Irani learnt the tricks of the film trade. In 1920, he produced his first film, Nala Damayanti, a Hindu mythological tale, and by 1930, he was an established producer. In an interview with B.D. Garga in 1980, Irani said he was inspired to make Alam Ara after watching the 1929 American film Show Boat, an early sound movie that mixed the silent format and spoken dialogue, marking a transition in filmmaking technology. Irani had no inkling that his project would lead to the evolution of what film scholar Devashree Mukherjee termed “a new cine-ecology”.

and laid the foundation of the Indian film industry. According to one estimate, says the writer,

it earned Rs 29 lakh – 72 times its investment.

Irani decided to adapt the play Alam-Ara, written by Joseph David Penkar (1876-1948), producer and playwright of the Parsi Imperial Theatre Company. A romantic drama featuring a gypsy girl, a prince, his father, the king and his two wives, a Sufi prophecy on childbirth and much jealousy, love and longing, it was different from the mythological films that Irani had hitherto produced. He also chose everyday Hindustani (a mix of Hindi and Urdu) as its language instead of Gujarati or Marathi. Post Alam-Ara, Hindustani became the standard language of Bombay’s film industry.

Irani wanted to cast his frequent collaborator, Sulochana aka Ruby Myers, as Alam-Ara, but Myers was not proficient in Hindustani. This compelled him to look for a new heroine who would not only be fluent in the language but also look the part of an exotic gypsy girl. He found her in Zubeida (1911-1988), a popular actress of the 1920s and 30s. For the male lead, Irani opted for Master Vithal (1906-1969), a star from silent cinema.

Alam-Ara set new technical trends in Indian cinema. American sound recordist Wilford Deming landed in Bombay to set up the imported recording equipment and record the sound. Perhaps Deming’s Rs 100-per-day fee was too much for Irani and soon he was recording the audio track himself, no easy task, as dialogues were recorded live and early generation microphones had to be hidden within the actors’ costumes. But Irani was unstoppable. He decided to shoot the film at Jyoti Studio, Bombay, located near busy railway tracks, and chose to work only between 1 am and 4 am, when the local train services were suspended. Perhaps this was the first instance of night shifts, which later became standard practice in the Indian film industry. Additionally, actors had to adjust to delivering lines in a more controlled manner, a shift from the exaggerated expressions used in silent films.

Irani also recorded the film’s seven songs with Wazir Mohammad Khan singing De de khuda ke naam pe pyaare, the first-ever song in Hindi cinema. The film’s leading lady Zubeida sang some of the other songs. Though the now-lost film didn’t mention a composer or lyricist in its credits, later media reports and Saregama’s website suggest that B. Irani and Feroz Shah Mistry were the composers. All of this was a secret until the film, distributed by Sagar Movietone, was released at Majestic Cinema. The layered promotion of the film, including skilfully written copy (All Living, Breathing 100%, Talking) upped expectations. The audience was so thrilled to see the characters speak and sing that police had to be posted to manage the crowd. Needless to say, the 124-minute Alam-Ara, made at a cost of Rs 40,000, was a superhit. According to one estimate, it earned Rs 29 lakh – 72 times its investment.

teacher, a kerosene inspector and a seller of musical instruments.

What Alam Ara did for Indian cinema

Film scholar Shoma Chatterjee writes, “With the release of Alam Ara, Indian cinema proved two things — films could now be made in regional languages that local viewers could understand; and that songs and music were integral parts of the entire form and structure of the Indian film.” The film employed the Tanar sound system, which recorded sound directly onto the film, a groundbreaking technology at that time. It also introduced playback singing to Indian cinema, with De de khuda ke naam pe pyaare, which used only a tabla and a harmonium.

Alam Ara established ‘song and dance’ as an integral part of Indian cinema. As film writer Jameela Siddiqui writes, “Film music established itself as the music of the masses. Unlike in Western countries, where audiences from classical and popular music are drawn from different sections of the society, Indian film music had an appeal right across the social divide, becoming a vital part of a collective cultural heritage.”

Alam Ara was a huge box office hit, attracting large crowds and solidifying the popularity of talkies. It laid the foundation of the Indian film industry. The success of the film not only marked the birth of the talkie in the Indian Subcontinent but also pushed ‘Indianness’ onto the screen, showcasing Indian culture and stories, and actors who could speak Hindustani. It also framed the multi-cultural ecosphere of the Indian film industry. Ardeshir Irani was a Parsi. The film was based on a Parsi play written by Joseph David, a Jew. It was made in the Hindustani language. Master Vittal, the hero, was a Hindu from Maharashtra, while Zubeida was a Muslim.

Lost to posterity

Unfortunately, no prints of Alam Ara survive. India has a shoddy record in preserving films. Many pre-1950 Indian films are lost, in fact, as much as 70 per cent is estimated gone. Most of the 1,138 silent films made between 1912 and 1931 do not exist anymore. The film archive at Pune has managed to archive only 29 of them. In 2017, the British Film Institute’s Shruti Narayanswamy declared Alam Ara as the most important ‘lost film’ of India. In 2022, a group of archivists of Mumbai stumbled upon a film print machine used in the making of Alam Ara. However, they could not find any reels.

Alam-Ara was not just a film; it was a movement that transformed Indian cinema. Its pioneering use of sound cemented its place in history. As the first Indian talkie, it remains a symbol of innovation, resilience, artistic evolution and the multi-cultural ecosphere of the film industry.

References

1. The posters of ‘Alam Ara’ had these phrases.

2. https://www.hindustantimes.com/books/alamara-turns-93-101710444542829.html

3. https://garga-archives.com/writings/the-making-of-alamara-interview-with-ardeshir-irani/

(A journalist-turned media academician, the writer works as professor and regional director of the Indian Institute of Mass Communication, Dhenkanal, Odisha. His research interest areas include films, comic arts, media history and media sociology.)

from Webdoux

from Webdoux